Single-leg vs double-leg strength training for runners – do you have a leg to stand on?

Without strength training, a runner doesn’t have a leg to stand on…….In this article, we will be explaining why a runner’s strength program should use exercises that are performed on one leg, what the benefits are this type of exercise, and how to integrate them into a routine.

Without strength training, a runner doesn’t have a leg to stand on…….In this article, we will be explaining why a runner’s strength program should use exercises that are performed on one leg, what the benefits are this type of exercise, and how to integrate them into a routine.

Running requires a person to be fairly strong, just because you can walk without pain for a decent amount of time does not mean you can run for the same amount of time without getting injured. This is mainly due to differences in the biomechanics of each activity (1). To put it simply, when you walk, one foot is always in contact with the ground and at a certain point both feet are in contact with the ground. When you run only one foot is in contact with the ground at any time and there is a point where both feet are off the ground at the same time (2). The reduced contact point with the ground, and the ability to produce the muscular contraction necessary for the body to take off and land, means there is a much greater need for muscular strength when you are running than when you are walking (2).

Nearly half of runner’s injuries are due to a lack of strength (3), and several common running injuries such as patella femoral pain, IT band friction pain, plantar fasciitis, and ‘shin splints’ can be reduced by improving a runner’s strength (4, 5, 6, 7). We covered how strong you need to be to run and how to assess your own strength in a previous article, which you can find here.

The question here is, as running is an activity that depends on only landing on one leg at a time, is there a major benefit to doing strength training that focuses on exercises using one leg at a time? The answer here is unsurprisingly yes, most runners will benefit from performing exercises that focus on using one leg at a time, however, they should not be the sole focus of a runner’s strength program (1). When performing exercises using two legs, because of the strong base of support that comes from having two feet on the ground and the number of muscles recruited the overall load that can be lifted is more. When an exercise is performed on one leg, each leg can generate a much higher force on its own than when the exercises is performed on two legs. This is known as ‘bilateral deficit’ (1, 8). Due to the increased force generated while performing exercises on one leg there will be more muscle fibres recruited which may lead to increased strength gains in single-leg tasks (such as running). There are also several other benefits to performing strength exercises on one leg;

The question here is, as running is an activity that depends on only landing on one leg at a time, is there a major benefit to doing strength training that focuses on exercises using one leg at a time? The answer here is unsurprisingly yes, most runners will benefit from performing exercises that focus on using one leg at a time, however, they should not be the sole focus of a runner’s strength program (1). When performing exercises using two legs, because of the strong base of support that comes from having two feet on the ground and the number of muscles recruited the overall load that can be lifted is more. When an exercise is performed on one leg, each leg can generate a much higher force on its own than when the exercises is performed on two legs. This is known as ‘bilateral deficit’ (1, 8). Due to the increased force generated while performing exercises on one leg there will be more muscle fibres recruited which may lead to increased strength gains in single-leg tasks (such as running). There are also several other benefits to performing strength exercises on one leg;

Improved balance and control – when you stand on one leg, the way the body responds to stop you falling over includes the firing up of bits of the nervous system that help us balance and the increased activation of smaller muscles that help us retain stability. For instance, if you stand with both feet on the ground, most muscles are fairly relaxed, but if you lift one foot off there are a whole host of smaller stabilizing muscles that kick in to stop you falling over, mainly around the trunk and the hip of the standing leg (9). If these smaller muscles become more coordinated with the larger force-generating muscles then the movement will become more controlled and efficient.

Helping reduce strength asymmetry and improve injury rehabilitation – A comprehensive runner’s strength assessment often reveals a difference in strength and control between legs, often these imbalances can be a contributory factor in running-related injuries. Single leg exercises (as well as some trunk exercises) can be tailored to reduce this imbalance and produce a stronger and less injury-prone runner (1, 3). If you have an injury on one leg, training the other leg with single-leg exercises will even result in an increase in up to 11% strength in the injured leg, which will improve performance when returning to running (10).

Improving intermuscular coordination – The more coordinated the body’s movements, the more efficient it will be in motion. Single leg exercises give the body the opportunity to ‘fine-tune’ it’s movements and it’s muscular contraction timing. Exercises that mimic the running stride are most effective at improving performance in this area (1, 11)

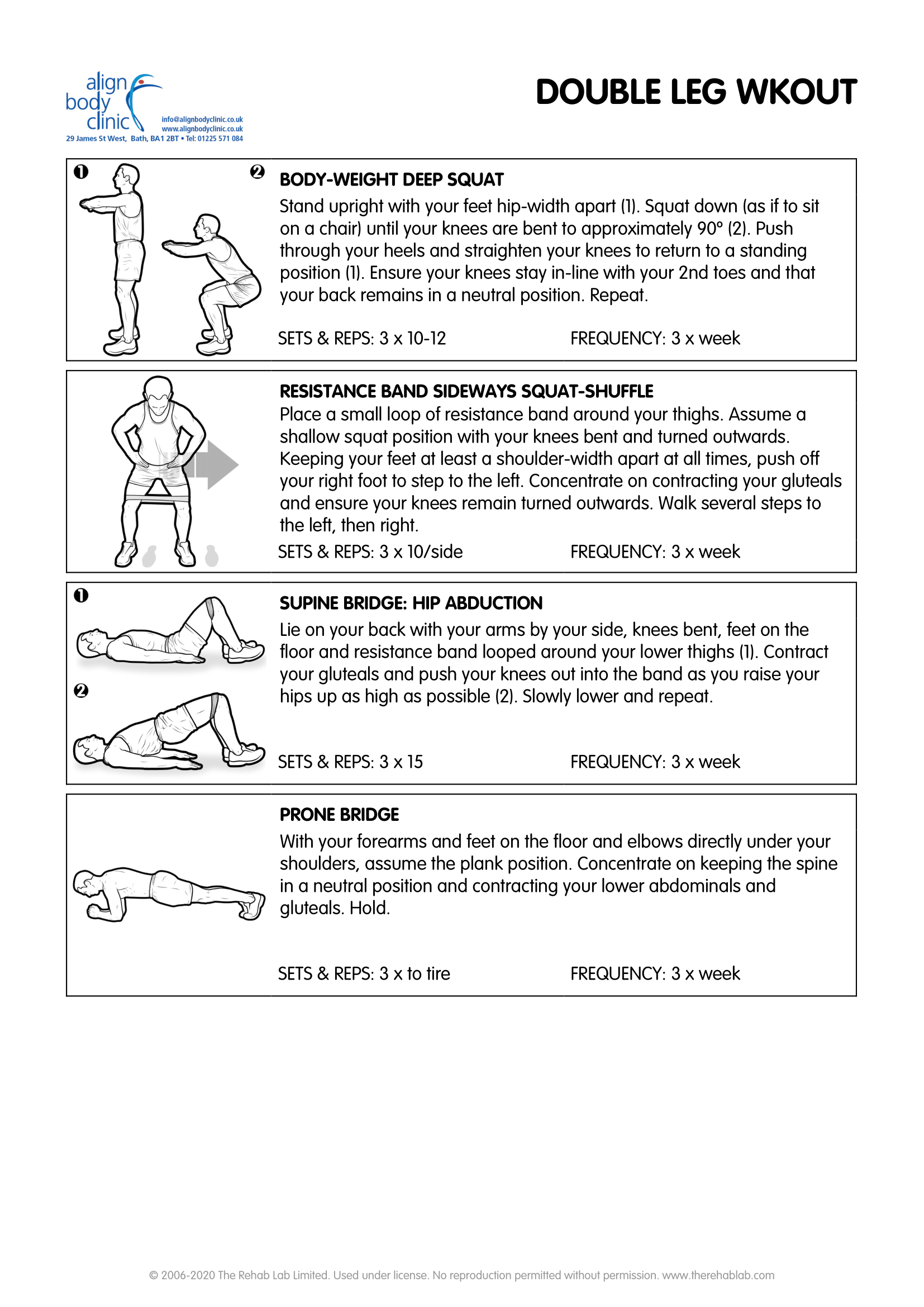

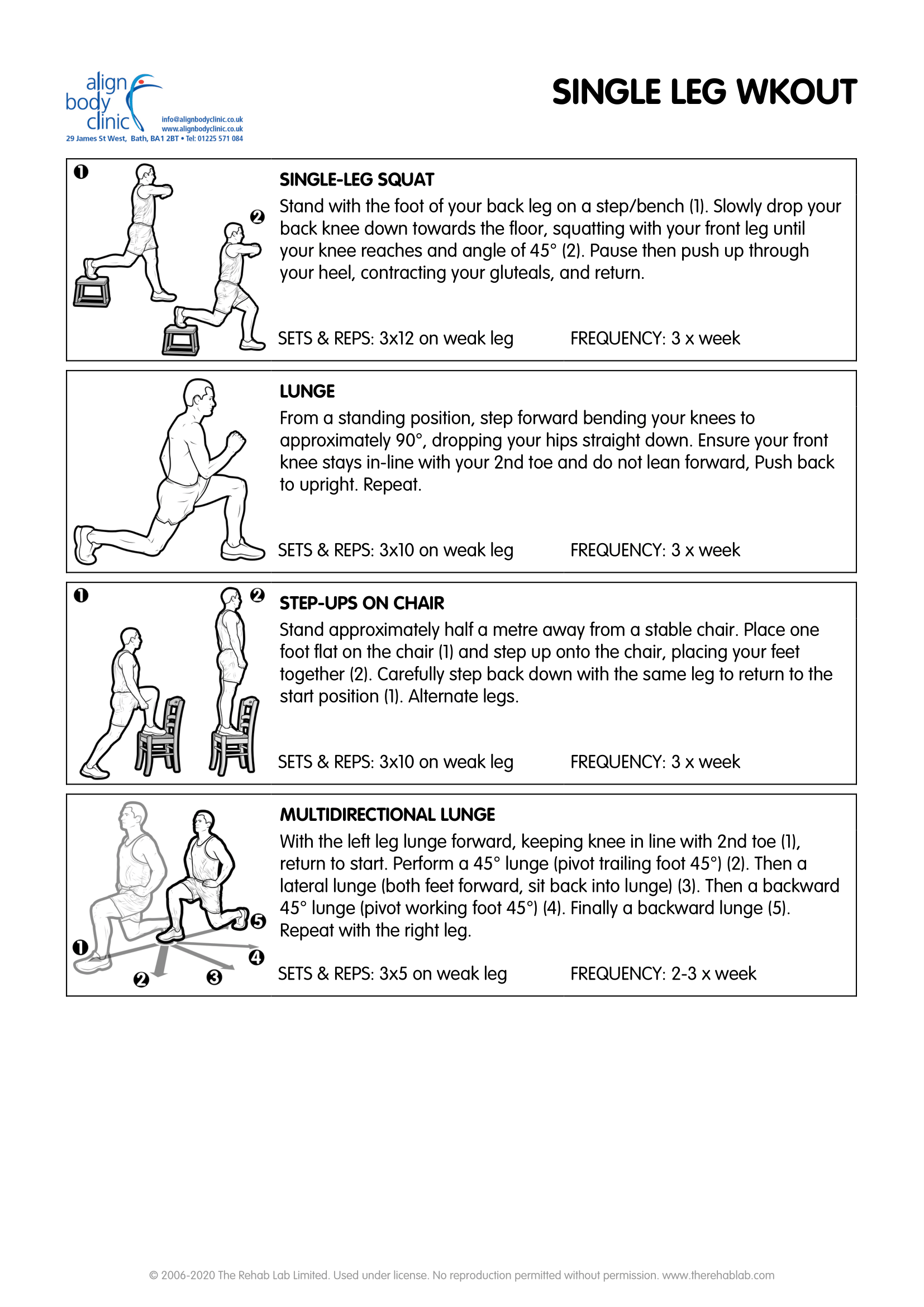

With that in mind, shouldn’t all the exercises runners do to improve their strength be single leg based? The answer here is no, a runner should include both double leg and single-leg exercises in a strength program, however, given the runner’s needs there may be more weight given to one or the other (1, 11). For instance, if a runner needs to improve strength in general then bilateral exercises that recruit a lot of fibres are better, but if a runner lacks control or core strength then they may be better off incorporating single-leg exercises. Only a comprehensive review of a runner’s training regime coupled with a full assessment of their muscular performance will be able to decide the most suitable exercises for them.

However, a simple test can give you a rough idea of where to place your training focus.

Have a go at the sit to stand test pictured here and look to see;

- If you can do the full 20 on each leg – If not then use the single leg program below on both legs to get up to the full amount.

- If you can do the same amount on each leg – If not then some single-leg exercises on the weaker side would help (3 sets on the weaker leg, 1 set on the stronger one)

- If you are ‘stable’ on both legs, you may find one (or both) leg seems to lack power, or you notice the knee on the standing leg drifts in towards the other knee. If so then you may need to do some more hip/glute or trunk stability work on the ‘less stable’ side, either using 1 legged exercises, or if both sides lack control then use the two-legged strength exercises in the program below.

- What do you have to do with your upper body? Does it lean over to one side? Do you have to throw your upper body forward to generate power? If so you will need to do more two-legged exercises from the program below.

(Click on the images of the programs to view)

At Align Body Clinic we offer runners who are injured (or runners just want to improve their running performance) an in-depth assessment to see if they are either making training errors or have areas of their body that need strengthening to help them perform better and with fewer injuries. We can then set up a treatment and exercise program that will result in them achieving the goal they have, whether it is to run without pain or improve endurance and speed. We use strength, endurance, and core stability testing, as well as analysis of training schedules and running styles, to help runners of all abilities to achieve their goals pain and injury-free. We can provide individualised treatment plans and exercise programs to suit all needs.

Is an injury stopping you from running, or has pain stopped you from achieving your running goals? If so why not book a running injury consultation with our expert osteopath Jay Ruddock.

References

1 – Blagrove R (2015). Strength and Conditioning for Endurance Running. Crowood Press, Wilts.

2 – Novacheck T F, (1997). “The Biomechanics of Running,” Gait & amp; Posture, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. Available at; https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/3/30/Running_gait.pdf

3 – Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. (2014) The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine;48:871-877.

4 – Prins, M. R.; van der Wurff, P. (2009). Females with patellofemoral pain syndrome have weak hip muscles: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 55, 9-15.

5 Fredericson M., Cookingham C. L., Chaudhari A. M., Dowdell B. C., Oestreicher N., Sahrmann S. A. (2000). Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 10(3):169–175

6 – Winkelmann, Z. K., Anderson, D., Games, K. E., & Eberman, L. E. (2016). Risk Factors for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in Active Individuals: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of athletic training; 51(12):1049-1052.

7 – Rathleff, M. S., Mølgaard, C. M., Fredberg, U. , Kaalund, S. , Andersen, K. B., Jensen, T. T., Aaskov, S. and Olesen, J. L. (2015), HL strength training and plantar fasciitis. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 25: e292-e300.

8 – Maarten F. Bobbert, Wendy W. de Graaf, Jan N. Jonk, and L. J. Richard Casius (2006). Explanation of the bilateral deficit in human vertical squat jumping. Journal of Applied Physiology 100:2, 493-499

9 – Saeterbakken AH, Fimland MS. (2012). Muscle activity of the core during bilateral, unilateral, seated and standing resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol, May;112(5):1671-8.

10 – Manca A, Dragone D, Dvir Z, Deriu F. (2017). Cross-education of muscular strength following unilateral resistance training: a meta-analysis. Eur J Appl Physiol, Nov;117(11):2335-2354.

11 – Young WB (2006). Transfer of Strength and Power Training to Sports Performance. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance; 1:74-83