Why a slipped disc is not possible…

It is a common occurrence for us to hear a patient say that they ‘had a slipped disc, but my previous osteopath/chiropractor/physio/doctor put it back in for me’. While we are always happy to hear of people’s pain being resolved there is a slight problem with that statement, the slight problem is that it cannot be true……..Why, you ask? Well we hope to explain this below.

It is a common occurrence for us to hear a patient say that they ‘had a slipped disc, but my previous osteopath/chiropractor/physio/doctor put it back in for me’. While we are always happy to hear of people’s pain being resolved there is a slight problem with that statement, the slight problem is that it cannot be true……..Why, you ask? Well we hope to explain this below.

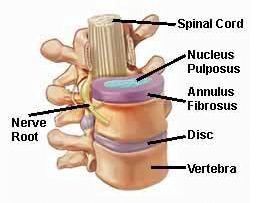

When we talk about discs we are talking about the intervertebral discs that are situated between the vertebral bodies, the reason we have them instead of a bony joint is that they allow for a wide range of subtle movements while simultaneously limiting excessive movements and resisting/dampening compression of the spine as a whole. The spine must have a certain degree of protection from movement to ensure the spinal cord is not at risk but also needs to be mobile enough to support movement of the body in general, the soft tissue construction of the discs help allow both these things to happen at the same time.

The discs are made up of three elements, the tough fibrous outer layers called the annulus fibrosis, the comparably liquid centre called the nucleus propulsus, and on the top and bottom a much stiffer area of fibres called end plates that structurally bind the discs to the vertebral bodies above and below. The structural resilience of the disc to almost any type of force, the surrounding ligaments, and the extremely strong attachment to the adjacent vertebrae mean that the disc cannot ‘slip’ anywhere. Whatever happens to it, it is staying where it is, so if someone tells you that they can put your disc back in then they don’t understand how a disc behaves………This is further backed up studies that show that to even compress a disc (in younger people) 1mm it takes forces of around 760lbs!

So can you get pain from a disc and why does it happen?

When you hear someone has a ‘slipped disc’ what would be more accurate would be that they have a disc pathology where the properties of the disc have become altered and the results are now producing pain. The way this happens is through disruption to the balancing act of the annulus and the nucleus.

When you hear someone has a ‘slipped disc’ what would be more accurate would be that they have a disc pathology where the properties of the disc have become altered and the results are now producing pain. The way this happens is through disruption to the balancing act of the annulus and the nucleus.

The outer tougher annulus fibres are arranged concentrically (although are not complete circles, many are incomplete) and provide much of the resilient properties of the disc. The fibres are thicker and more ‘complete’ at the front of the disc than at the back or the sides.

As the spine moves or is compressed the nucleus propulsus has pressure exerted on it, but due to its viscosity its volume cannot be compressed, rather it exerts pressure on the neighbouring fibres of the annulus fibrosis. This pressure is (in an intact disc) is resisted by the elastic strength of the annulus, this balance of pressure and resistance creates the disc’s strength to absorb load.

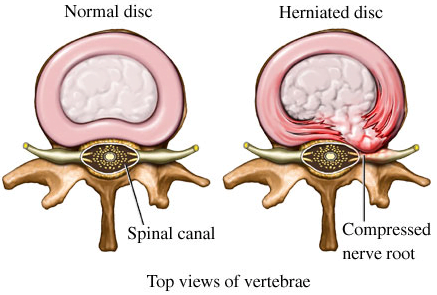

Disorder of these properties causes a chemical change in the annulus and the nucleus resulting in the nucleus propulsus being unable to retain water and then being able to infiltrate the surrounding fibres of the annulus. The inner fibres of the annulus have no nerve supply that can signal pain so only when the nucleus is able to reach the outer fibres of the annulus will there be any pain felt from this process. This pain can be felt as a chronic strong ache either independent of or as a result of certain movements. A more acute sudden pain that may be accompanied by nerve pain felt in the arms or legs (depending on the spinal level affected) is more likely to be a disruption of the very outer layers of the annulus leading to the nucleus creating either distension of the outside of the disc or actually leaking out from the disc and affecting the spinal cord or it’s exiting nerves.

As the structure of the disc has now changed it becomes less able to resist compression and movement forces resulting in most of the forces being focused on the annular fibres at the back of the disc where they are weaker. This then causes further stress on the disc and an increase in the level of movement possible resulting in the workload of the surrounding ligaments, muscles and joints of the spine increasing meaning they too are more vulnerable to acute injuries and pain. The increased load on other tissues and the pain that they can generate can lead to a more chronic pain situation which people would usually describe as a ‘bad back’.

As the structure of the disc has now changed it becomes less able to resist compression and movement forces resulting in most of the forces being focused on the annular fibres at the back of the disc where they are weaker. This then causes further stress on the disc and an increase in the level of movement possible resulting in the workload of the surrounding ligaments, muscles and joints of the spine increasing meaning they too are more vulnerable to acute injuries and pain. The increased load on other tissues and the pain that they can generate can lead to a more chronic pain situation which people would usually describe as a ‘bad back’.

The more acute and sudden occurrence of the events described above where the nucleus affects the very outer fibres of the annulus, or there is injury to other structures of the spine are usually what people would describe as a ‘slipped disc’. If a practitioner such as an osteopath was able to rather quickly help resolve the situation then they did not ‘put the disc back in’, it is much more likely that they treated a problem stemming from the joints or muscles.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

Sources

Bogduk, N., (2005). Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Levangie, P. and Norkin, C. (2005). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed). F. A. Davis, Philadelphia.

Urban, J., Roberts, S., (2003). Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 5(3), pp120-130.