‘Wear and Tear’ on the spine

What is Wear and Tear of the Low Back?

Wear and tear of the low back is a ‘catch-all’ term used to describe changes in the intervertebral discs and the spine as we get older. The term is commonly used to describe the results of an MRI or X-ray to a person who has been experiencing low back pain. Results like this from an MRI are only a snapshot of the structures in the spine and do not indicate a limit on the ability of the spine to perform effectively or place a limit on a person’s capacity to improve any back pain they may be having.

The use of the term ‘wear and tear’ when attempting to describe MRI results has been shown to be detrimental to a person’s recovery from back pain and therefore should be replaced with ‘age-related changes’. Age-related changes in the spine can be present without any pain.

Many people who have back pain arrive at our practice after being told by their doctor that they have ‘wear and tear’ in their spine, or that ‘it is part of getting older’. Often, they will have had an x-ray or an MRI showing that ‘some of the discs in the back are wearing out’.

What we will explain in this article is why the term ‘wear and tear’ is not only inaccurate but also that it is harmful to low back pain sufferer’s future outcomes. We also will explain what to do if you have low back pain and have been told that your MRI shows you have ‘wear and tear’.

What does ‘wear and tear’ of the low back mean?

In the broadest sense, it means that the person explaining your MRI results to you is paraphrasing to explain in layman’s terms the technical language contained in the radiologist’s report of your imaging. If there has not been a traumatic onset of the pain then the language that the radiologist is using could more accurately be described as ‘age-related changes’. If you get to see the written report that accompanies your MRI then it will commonly have words such as ‘degenerative disc disease’, ‘spinal stenosis’, or ‘bulging/prolapsed discs’. In the context of hearing the words ‘wear and tear’, these terms are describing a set of changes that happen to the vertebral column as we get older.

What happens to the spine as we get older?

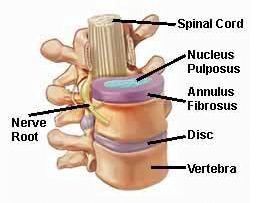

The intervertebral discs and vertebrae from the principle joints in your spine, at each level of the spine there is one intervertebral disc and two ‘facet joints’.

Their structure and their relationship are designed to allow the spine to move and to cope with the loads we place on our backs over the course of a lifetime (1). Each disc is made up of three elements;

NUCLEUS PROPULSUS – This is the more fluid centre of the disc, it is said to have the consistency of toothpaste. Its main function is to dissipate force by its fluid nature, a bit like a water balloon if you squeeze it then it will move in any direction.

NUCLEUS PROPULSUS – This is the more fluid centre of the disc, it is said to have the consistency of toothpaste. Its main function is to dissipate force by its fluid nature, a bit like a water balloon if you squeeze it then it will move in any direction.

ANNULUS FIBROSIS – This part of the disc is made up of tough collagen fibers, precisely arranged in ways to resist the pressures placed upon it by the movement of the nucleus proplusus.

VERTEBRAL ENDPLATES – These form the top and bottom of the disc and are mostly cartilage, they are extremely tough and are the barrier between the nucleus and the vertebrae.

Only the outer few millimeters of the annulus has nerves that transmit sensation and pain. (1, 2). As we get older the vast majority of us begin to show changes in these structures, leading to a change in how they perform their tasks. The nucleus of the disc becomes less fluid, elastic and ‘spongy’, changes to its structure make it much ‘drier’ and therefore less able to cope with the forces exerted upon it. This results in the annulus having to take up more of the strain, resulting in damage. This damage creates ‘fissures’ in the annulus allowing the nucleus to move more freely to exert pressure on the outside of the disc (where the nerves that transmit pain are located), this is how ‘bulging discs’ occur. These changes also lead to an increase in the amount of pain-producing nerves around the disc. (3). The facet joints and vertebral bodies also show changes, they begin to lose their cartilage and instead deposit bone to compensate, changing the shape of the bone, this is the process that leads to osteoarthritis and what is referred to as spinal stenosis.

These changes are often referred to as ‘degenerative disc/joint disease’, however, the changes seen are actually the body reacting and adapting to the stresses exerted upon it over the course of our lifetime (1, 2).

Is my back sore because of wear and tear of the spine?

Degenerative findings from MRIs are common in people who have no pain in their back, meaning that the presence of ‘wear and tear’ does not automatically mean your pain is due to those findings. A study in 2015 (4), examined MRI results from people who had no back pain and found that, among other findings, that at age 50 80% of people showed disc degeneration and 60% had a disc bulge. This study and others (5, 6) would indicate that positive findings of age-related changes in the low back are not the exclusive cause of low back pain.

Degenerative findings from MRIs are common in people who have no pain in their back, meaning that the presence of ‘wear and tear’ does not automatically mean your pain is due to those findings. A study in 2015 (4), examined MRI results from people who had no back pain and found that, among other findings, that at age 50 80% of people showed disc degeneration and 60% had a disc bulge. This study and others (5, 6) would indicate that positive findings of age-related changes in the low back are not the exclusive cause of low back pain.

When referring to the results of an image of the spine the term ‘wear and tear’ is not appropriate as it carries several inaccurate connotations, such as ‘there is nothing that can help’, ‘you just have to live with it’, ‘it won’t get better’. People who are told this often report that they think their situation will only get worse over time leading to not engaging with therapies that may be able to help (7)

Then why is my low back sore?

Low back pain can be caused by many factors, such as excessive loading of the structures of the low back through heavy lifting, sitting at a desk for long periods, or exercise habits. Often a person’s pain is due to a combination of factors that have no single tissue or structure that is identifiable as the source of the pain, but that can lead to a pattern of pain (over three months duration) becoming chronic (8).

What can be done about my pain?

As findings of ‘wear and tear’ of the low back do not always indicate the source of the pain it can be valuable to get an expert to assess your symptoms and examine how the back functions. An MRI is a static image that will let you know what the structures involved look like, and in some cases (disc herniation (4)) will be accurate in describing symptoms, however, it will not tell you how the low back is performing in movement, bending and under certain loads such as walking/lifting etc. Having an expert such as an osteopath take an accurate history of your pain, examining how it performs can often lead to a good understanding of a person’s pain. In most cases, your osteopath will then be able to recommend simple interventions such as joint mobilisation, home exercise, and advice on prevention that have been shown to be successful in helping relieve chronic low back pain (9, 10, 11). Each intervention is unlikely to succeed on its own and commonly combining interventions will be more successful in avoiding a recurrence of your symptoms.

What is our experience as osteopaths?

At Align Body Clinic we commonly see patients who have back pain, they then get an MRI or an x-ray which shows ‘wear and tear’ or ‘worn discs’ and are told that it is just part of aging, and to accept it. Often this is not the full picture and can lead to an incorrect assumption that nothing can be done. We find it to be much more productive to take an individualised approach to each case, considering the person’s age, occupation, previous injuries etc. This approach, coupled with a thorough physical examination and the results of the x-ray/MRI can lead to a much clearer picture of what may be done to reduce the pain and return the person to normal activities. Often our patients achieve a full recovery or at the very least we can control their pain through manual treatment, exercise, and advice specific to their situation.

In cases where there are significant structural changes in the spine, it is commonly possible to alter the function of the unaffected areas, such as the midback, hips, etc and produce a reduction in pain levels and increased movement. Each patient’s situation is different, only after a thorough assessment is it possible to know what the best course of action may be.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References

1 – Bogduk, N., (2005). Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

2 – Levangie, P. and Norkin, C. (2005). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed). F. A. Davis, Philadelphia.

3 – Urban, J., Roberts, S., (2003). Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 5(3), pp120-130.

4 – Brinjikji, W. et al (2014). Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. Available at; http://www.ajnr.org/content/36/4/811.

5 – Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, et al (2010). Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain. Spine J;10:200–08

6 – Wiesel SW, Tsourmas N, Feffer HL, et al (1984). A study of computer-assisted tomography. I. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976);9:549–51.

7 – Sloan, Tim & Walsh, David. (2010). Explanatory and Diagnostic Labels and Perceived Prognosis in Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine. 35. E1120-5. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e089a9.

8 – Khan, R. Hargunani et al. (2014). “The lumbar high-intensity zone: 20 years on.” Clinical Radiology, 6 June, 551-558

9 – Choi, J et al (2014). The Effects of Manual Therapy Using Joint Mobilization and Flexion-distraction Techniques on Chronic Low Back Pain and Disc Heights, available at; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4155230/

10 – National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG59]. London: NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59

11 – Anthony Delitto. et al. (2012) “Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, ;42(4):A1-A57. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.0301 (resource – guideline based on level 1a and level 1b evidence)