Sciatica – What is it? What causes it? What do I do if I have it?

Please note this article is intended for information only, it is not intended as a diagnosis for pain, if you have symptoms that are undiagnosed then you must seek advice from a professional before taking any action. This article covers selective causes of sciatica, if you have pain post trauma, pain accompanied by fever or weight loss, changes in your bladder or bowel habits, numbness around your genitals or anus, or rapidly worsening symptoms you must immediately seek medical assistance).

What is sciatica?

What is sciatica?

Sciatica is entrapment or irritation of the sciatic nerve leading to changes in how the nerve functions; this might mean pain, weakness or numbness down one or both legs. The technical term for sciatica is ˜lumbar radiculopathy’ as other nerves that originate from the lumbar spine apart from the sciatic nerve may be affected; this article will be focusing on the common causes of sciatic nerve irritation.

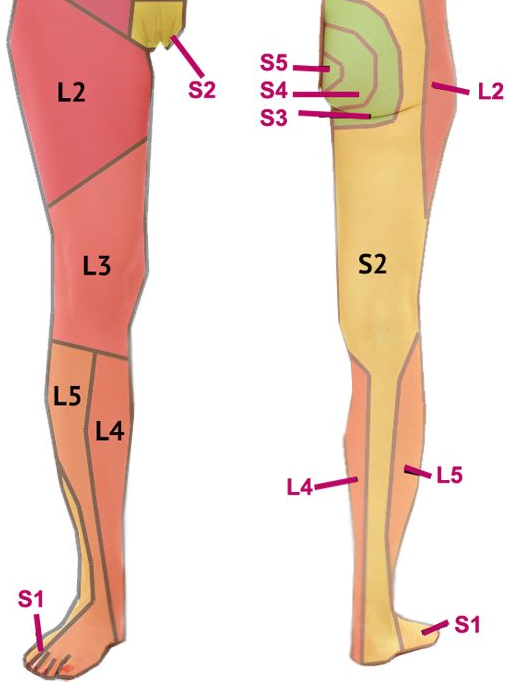

The sciatic nerve starts as it branches off from the spinal cord at the level of the lowest two lumbar vertebrae (L4 and L5) and the first three sacral levels (S1-3 (1).

Once all its branches join up, as it travels through the pelvis, it becomes the thickest nerve in the body (1), its function is to supply and receive information from the muscles and skin of the back of the thigh and nearly all of the lower leg.

What causes it?

If there is any pressure around the sciatic nerve, or there is inflammation from tissue damage (muscle, ligament, joint dysfunction or disc injury) it can affect how the nerve performs, commonly resulting in pain, numbness or weakness in the areas the nerve is associated with. The location of the symptoms will depend on what is causing the irritation to the nerve.

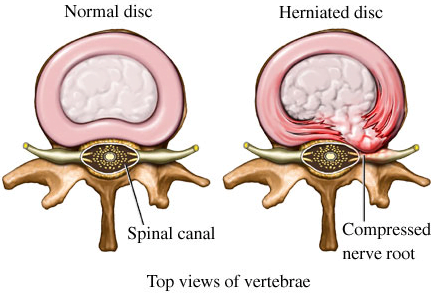

Intervertebral disc injury

Intervertebral discs lie between the vertebrae; they are made up of very tough fibrous material and a more gelatinous centre. If the disc becomes damaged, either through repeated actions (improper lifting, bending etc.) or from trauma this can result in the nerve associated with that spinal level being affected. In the past it was assumed that the disc was compressing the nerve as it exited the spine but it is also possible that that the nerve is being affected by inflammation (2).

If the pain is from a disc injury it will most likely be in a very specific area of the skin (dermatome) or muscle (myotome) of the leg associated with that nerve.

98% of low back disc injuries originate from the L4/L5 or L5/S1 levels of the low back making the most common symptoms are a sharp shooting pain, numbness or weakness in the lower leg and toes, there may be severe or mild low back pain too often made worse by bending forwards. The more common age groups to experience a disc injury are 25-45, with 35-45 being the most common (3). Often the person will have had a few episodes of low back pain in the past. A good way to tell if you might have a disc injury is if you have pain in the low back and leg when you cough, sneeze or strain to pass a stool.

A disc injury is relatively easily diagnosed by an osteopath or a doctor, MRI imaging is usually only used if the symptoms persist without change after four weeks (3). Treatment is based around pain management in the early phases (medication, activity modification), then progresses into getting the patient more active and mobile and finally addressing the problems that may have contributed to the problem in the first place (biomechanics, lack of mobility/strength). Very rarely is surgery needed (2-4%) of cases (3).

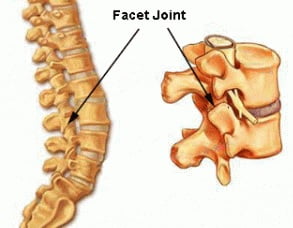

Facet Joint Syndrome

Zygapophysial or facet joints are part of the mechanism over how the spine produces movement. The joint itself and its soft tissue capsule can become inflamed due to being pinched or entrapped in the joint (4, 5). Often this condition produces only low back pain but it is possible that it may irritate the spinal nerve close by and produce pain through the buttock and into the back of the thigh. If the pain is being produced by a facet joint injury it rarely goes beyond the knee and may be more dull and achy than sharp and shooting (3). One indicator of a facet joint injury is that the back and thigh pain may get worse if you bend backwards.

Zygapophysial or facet joints are part of the mechanism over how the spine produces movement. The joint itself and its soft tissue capsule can become inflamed due to being pinched or entrapped in the joint (4, 5). Often this condition produces only low back pain but it is possible that it may irritate the spinal nerve close by and produce pain through the buttock and into the back of the thigh. If the pain is being produced by a facet joint injury it rarely goes beyond the knee and may be more dull and achy than sharp and shooting (3). One indicator of a facet joint injury is that the back and thigh pain may get worse if you bend backwards.

Facet joint injuries are easily identified by an osteopath and are usually relatively easy to resolve with osteopathic techniques (10). We regularly acheive positive reults in the treatment of patients with facet joint pain and sciatica.

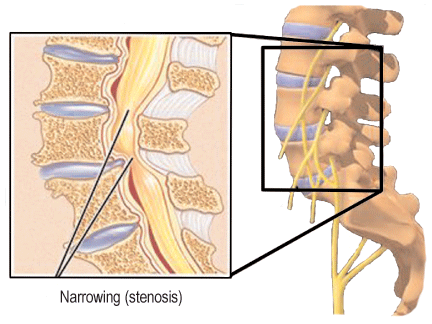

Spinal Stenosis

Low back Stenosis is a condition where the space in which the spinal cord or the exiting spinal nerves occupy has been narrowed, causing disruption and irritation to the sciatic nerve. This is due to a loss of height in the discs, and changes in the shape and size of the vertebrae and ligaments of the spine (6). It is primarily a result of aging and maybe referred to as ‘wear and tear’ of the spine. Lumbar stenosis is mostly seen in people over 50 (3, 4) and is estimated that 3-4% of people reporting to a doctor for low back pain have a form of stenosis (7).

The symptoms experienced are varied depending on the change in shape or narrowing of the area where the nerve is, therefore symptoms can be varied. Most commonly people with lumbar stenosis have back and leg pain described as burning and possibly cramping. Early symptoms are usually in the buttocks and later it spreads to the lower legs and feet (3). The pain may be on one or both sides. One clue that may indicate if you have stenosis of the spine is that the pain gets worse with activity and is relieved by rest and bending forwards (bending forwards opens up the space where the nerve is and reduces the irritation therefore the pain) (8).

The symptoms experienced are varied depending on the change in shape or narrowing of the area where the nerve is, therefore symptoms can be varied. Most commonly people with lumbar stenosis have back and leg pain described as burning and possibly cramping. Early symptoms are usually in the buttocks and later it spreads to the lower legs and feet (3). The pain may be on one or both sides. One clue that may indicate if you have stenosis of the spine is that the pain gets worse with activity and is relieved by rest and bending forwards (bending forwards opens up the space where the nerve is and reduces the irritation therefore the pain) (8).

Osteopaths and doctors can assess a person they suspect of having lumbar stenosis but ultimately diagnosis is made through X-ray, or more commonly MRI (3). Conservative treatment is considered first, using techniques such as massage, spinal mobilization and exercises. Even without treatment a patients symptoms may remain stable or even improve over time (3, 4). The success rates for surgery in the case of lumbar stenosis remain controversial (3, 4), although it is a recommended treatment for severe cases. (11).

Piriformis Syndrome

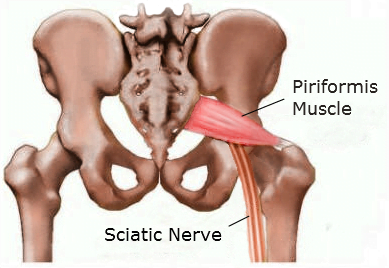

The piriformis is a muscle which is attached to your sacrum and your femur, as the sciatic nerve travels through the pelvis it passes in front of the piriformis through a narrow space called the sciatic notch. If the piriformis muscle is strained or damaged the resulting inflammation may irritate the sciatic nerve. Also if it is shortened due to repetitive habits (sitting, walking) then the nerve may be ‘compressed’ by the muscle.

The piriformis is a muscle which is attached to your sacrum and your femur, as the sciatic nerve travels through the pelvis it passes in front of the piriformis through a narrow space called the sciatic notch. If the piriformis muscle is strained or damaged the resulting inflammation may irritate the sciatic nerve. Also if it is shortened due to repetitive habits (sitting, walking) then the nerve may be ‘compressed’ by the muscle.

The symptoms of piriformis syndrome are usually pain in one buttock and tingling or numbness down the back of the thigh and leg. There may or may not be back pain. You can get an indication of whether or not you may have piriformis syndrome by pressing into the buttock on the affected side, if it reproduces your leg symptoms then the piriformis could be the reason (3, 8).

Piriformis syndrome is usually easily diagnosed by an osteopath and responds well to techniques that stretch and massage the piriformis as well as addressing the biomechanics of the pelvis and spine (3).

What do I do if I Have Sciatic Pain?

There is no easy answer to this question; it depends on the severity of the symptoms, how long you have had them and if they are getting better or worse. As the symptoms represent a problem with a major nerve in the body they must be taken seriously as long term effects of a damaged sciatic nerve such as weakness or chronic pain can adversely affect a person’s ability to work or lead an active life (9). If you have sciatic pain that is not getting better, or keeps coming back then our advice would be to seek expert advice from an osteopath or your GP as soon as possible to get an accurate diagnosis and begin treatment to get rid of the pain.

Sciatic pain can be very distressing, especially as it can be severe and debilitating. Even if you have severe sciatic pain from a lumbar disc problem, most of them (75%) get better within 6 months, with 50% improvement coming in the first 6 weeks (3). We always find the earlier you get an accurate diagnosis and start the appropriate treatment the better the outcome due to appropriate advice or what you should and shouldn’t do, safe ˜hands on’ treatment, and the prescription of exercises to help you be more comfortable.

Sciatic pain is a very common reason to attend an osteopathic clinic and we successfully treat several patients each month complaining of these symptoms.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References

1 – Snell, R. et al (2008). Clinical Anatomy by Regions (8th edition). Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

2 -Kuslich et al at (1991). The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operation on the lumbar spine using local anaesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am, 22, p181-187.

3- Carnes, M, & Vizniak, N. (2011). Conditions Manual. Professional Health Systems, Canada.

4- Souza, T. (2009). Differential Diagnosis and Management for the Chiropractor. 4th ed, Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

5 -“ Magee, D. Zachazewski, J. and Quillen, W., 2009. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, Missouri, Elselvier.

6 – Truumees, E. (2005) Spinal stenosis: pathophysiology, clinical and radiologic classification. Instr Course Lect. 54:287-302.

7- Hart, L et al (1995). Physician office visits for low back pain. Frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a US national survey. Spine, vol 20, pp11-19.

8- Goodman, C. Snyder, T. (2000). Differential Diagnosis in Physical Therapy. Elselvier, Philadelphia.

9- NICE Guidelines (2015). Sciatica (lumbar radiculopathy), available at http://cks.nice.org.uk/sciatica-lumbar-radiculopathy#!topicsummary.

10- Leininger, B. et al (2011). Spinal Manipulation or Mobilization for radiculopathy: A Systematic Review. Phys Med Clin Rehabil Clin N Am, Volume 22, Issue 1, Pages 105–125.

11- Kreiner, D. et al (2011). NASS Clinical Guideline Committee, Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spine Stenosis. Available at, https://www.spine.org/Documents/ResearchClinicalCare/Guidelines/LumbarSt….

What is sciatica?

What is sciatica?