Patella Tendon Pain – Runner’s Knee

Everybody has probably experienced some kind of knee pain, most of us will have had a bit of tendonitis in the knee after overdoing some kind of activity. It can be pretty sore for a few days, making it hard to get up and down the stairs and getting up out of a chair but disappears quickly with a bit of rest. However, what if it continues to hurt, or even gets worse? If the pain doesn’t subside then it may stop you enjoying your chosen sport or hobby, which can be very frustrating. This article seeks to explain what causes ongoing or worsening pain in the patella tendon, how to categorize it, and how to get rid of it.

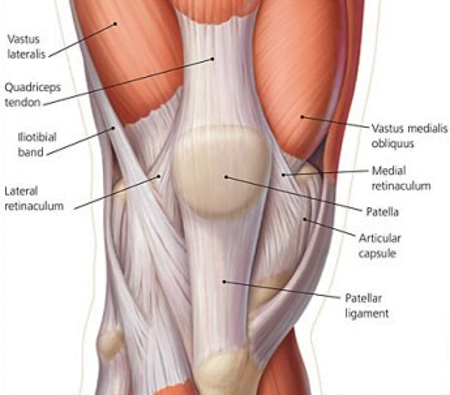

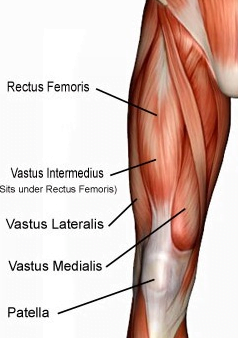

The patella tendon, such a workhorse, blessed with a very short but very wide shape, its fibres enable the quadriceps to exert and to resist very strong forces across the knee joint. This transmission of forces is vital in any activity that requires ‘high impact’ such as running or jumping and it is the patella tendon that has to cope with the brunt of this force (1).

The patella tendon, such a workhorse, blessed with a very short but very wide shape, its fibres enable the quadriceps to exert and to resist very strong forces across the knee joint. This transmission of forces is vital in any activity that requires ‘high impact’ such as running or jumping and it is the patella tendon that has to cope with the brunt of this force (1).

The nature of its high intensity workload can leave it vulnerable to injury and damage with 20% of people who regularly engage in high impact activities suffering from patella tendon pain (2), it also accounts for 1 in 20 running injuries (3).

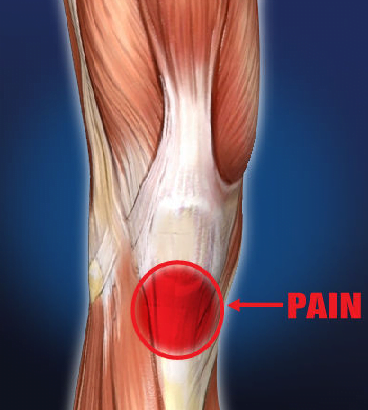

The pain is typically felt as the lowest part of the patella where it joins the tendon, first as general stiffness around the knee which becomes more focused on the tendon as it  progresses. Sufferers will often feel the pain after activity, especially going down hills or stairs, or after sitting with the knee flexed and then getting up (4). If the pain is temporary and transient, lasting just a few days then the pain is most likely to be caused by inflammation (tendonitis), which stimulates healing and adaption in the fibres of the tendon. If the pain is longstanding and pervasive it is usually the case that the tendon’s normal healing process has become disrupted, leading to a thickening and proliferation of fibres that have become ‘disorganised’ so they cannot cope with load as normal fibres would. This leads to pain and further trauma to the tendon when loaded (5).

progresses. Sufferers will often feel the pain after activity, especially going down hills or stairs, or after sitting with the knee flexed and then getting up (4). If the pain is temporary and transient, lasting just a few days then the pain is most likely to be caused by inflammation (tendonitis), which stimulates healing and adaption in the fibres of the tendon. If the pain is longstanding and pervasive it is usually the case that the tendon’s normal healing process has become disrupted, leading to a thickening and proliferation of fibres that have become ‘disorganised’ so they cannot cope with load as normal fibres would. This leads to pain and further trauma to the tendon when loaded (5).

So why would someone develop this type of condition? What can be done to lower the risk of suffering from it?

First of all this type of problem is usually on overuse injury where a person has increased the intensity, frequency or duration of their activity too quickly (‘new year resolution syndrome’). So one thing you can do is to carefully structure your exercise programme with a slow but steady progression (no more than 5% increase per week in any variable). Activities that stress the tendon most are deep squatting, stop/start sprinting and hill training for runners (4).

First of all this type of problem is usually on overuse injury where a person has increased the intensity, frequency or duration of their activity too quickly (‘new year resolution syndrome’). So one thing you can do is to carefully structure your exercise programme with a slow but steady progression (no more than 5% increase per week in any variable). Activities that stress the tendon most are deep squatting, stop/start sprinting and hill training for runners (4).

It is also possible that the biomechanics of your pelvis, hips, and ankles are having an effect on the forces that are exerted on the patella tendon. If the knee is misaligned (seen in over or under pronation of the feet and varum/valgus patterns in the knees) it can cause a whip or shear force in the patellar tendon when the knee is loaded, causing damage.

Likely causes for these imbalances include weak gluteal muscles (especially abductors), an imbalance in the quadriceps (weakness in the medialis, with tightness in the lateralis), or tightness in the hamstrings, hip flexors or calves. These can also be influenced by external factors such as improper footwear or training on unsuitable surfaces (4).

What can be done about it?

Well it depends on how long you have had the problem.

Well it depends on how long you have had the problem.

If it is acute (under 2 weeks) then it should be treated as any other tendonitis , by cutting back on activity levels, possibly avoiding the activity that gives it most pain, and icing the knee for15 mins, 3 times a day and after activity. For some people this will be enough to get rid of the pain, but sufferers should seek help from an osteopath or other manual therapy provider to get a proper assessment of underlying causes that may cause the pain to reoccur (4, 6).

If the pain has been present for longer, or it won’t improve with rest then it indicates that the tendon is struggling to heal itself and its fibres have become disorganised, this is called a tendinopathy (5). Most of the evidence for successful resolution of what can be a stubborn problem revolves around pain control, activity moderation and effective strengthening of the tendon in specific ways.

The first thing is to reduce the pain, modifying your activity, excluding high impact acivities, reducing the duration of training and only training twice a week are thought of as sufficient  controls (7). Another way to help control the pain and to begin to increase the tendon’s ability to deal with load is isometric or ‘held’ exercises. One study (8) showed that holding contraction on a leg extension machine (found in most gyms) four times for 45-60 seconds each can reduce the pain for up to eight hours.

controls (7). Another way to help control the pain and to begin to increase the tendon’s ability to deal with load is isometric or ‘held’ exercises. One study (8) showed that holding contraction on a leg extension machine (found in most gyms) four times for 45-60 seconds each can reduce the pain for up to eight hours.

Once the pain is under control then it is now that problems that have been identified in the sufferer’s biomechanics must be addressed with manual therapy and very specific stretching and strengthening exercises. One of the more effective ways to do this is to use eccentric exercise. Eccentric means the muscle is lengthening under tension, this is what happens to your quadriceps when you slowly lower yourself into a chair. A very specific exercise called a ‘unilateral eccentric decline squat’ has been shown to have good outcomes in terms of pain reduction and returning to their chosen exercise for up to 12 months (9). The example video above is very advanced, but there are several introduction levels and progressions that should allow most people to use this exercise.

After the person can tolerate the load demanded by the eccentric exercises then a return to more ‘activity specific’ and high impact exercise can be introduced before a complete return to full activity (7). Usually these steps are enough to get rid of the pain or at the very least minimize it so the person can continue with their chosen activity.

You can find a basic stretch and exercise guide to help with the care of patella tendon pain on our resources page.

What is our experience as osteopaths?

Patella tendonitis/tendinopathy can be a very stubborn condition to get rid of, however the evidence base for the steps explained above is pretty strong, so unless a patient has followed the recommended advice they may continue to suffer the pain and limited mobility associated with this condition. The most common reasons that people don’t get better are;

Patella tendonitis/tendinopathy can be a very stubborn condition to get rid of, however the evidence base for the steps explained above is pretty strong, so unless a patient has followed the recommended advice they may continue to suffer the pain and limited mobility associated with this condition. The most common reasons that people don’t get better are;

- Failure to address the underlying biomechanical factors (tightness or weakness in the hips/legs/pelvis/back)

- An over reliance on passive treatments, basically not using carefully prescribed, progressive strength exercises or activity level control, but relying on ‘hands on’ treatment from on osteopath, physiotherapist etc.

- Having an unrealistic expectation of the speed of recovery – usually resulting in stopping a treatment or exercise process too early (5).

Every case of patella tendon pain is different and needs expert assessment to determine the best course of action to suit that person’s individual situation, by getting good advice and following a structured rehabilitation program most people see huge changes in their pain levels and their ability to get on with life. You can find a basic exercise guide to help with patella tendon pain in our resources section.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

References

1 – – Levangie, P. and Norkin, C. (2005) Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed). F. A. Davis, Philadelphia.

2 – Magee, D. Zachazewski, J. and Quillen, W., 2009. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, Missouri, Elselvier.

3 – Taunton J. Ryan M. Clement D. McKenzie D. Lloyd-Smith D. Zumbo B. (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36, 95-101.

4 – Carnes, M, & Vizniak, N. (2011). Conditions Manual. Professional Health Systems, Canada.

5 – Cook L, Purdam R (2009). Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Jun 1;43(6):409-16.

6 – Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E, (2015). Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. Sep:1-33.

7 – Rudavsky, A. Cook, J et al (2014). Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee). Journal of Physiotherapy , Volume 60 , Issue 3 , 122 – 129

8 – Naugle, K.M., Fillingim, R.B., and Riley, J.L. 3rd (2012). A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. J Pain, 13: 1139–1150.

9 – Young M, Cook J, Purdam C, Kiss Z, Alfredson H, (2005). Eccentric decline squat protocol offers superior results at 12 months compared with traditional eccentric protocol for patellar tendinopathy in volleyball players. Br J Sports Med. Feb, 39(2):102-105