Knee Pain – What causes it, what to do if I have it, and how to prevent it.

Why would I get knee pain?

The knee is a site of several potential problems, some can be very hard to get rid of, some can be very easy. The structure of the knee joint and it’s relationship to other joints in the body means it is a common site of injury and pain (1). The knee must be able to provide stability and mobility, this results in it having at first glance a relatively simple structure, but when it’s performance under movement is analysed it is very complex. The knee works together with the hip and ankle to deal with bearing the weight of the body when it stands and moves.

The knee is a site of several potential problems, some can be very hard to get rid of, some can be very easy. The structure of the knee joint and it’s relationship to other joints in the body means it is a common site of injury and pain (1). The knee must be able to provide stability and mobility, this results in it having at first glance a relatively simple structure, but when it’s performance under movement is analysed it is very complex. The knee works together with the hip and ankle to deal with bearing the weight of the body when it stands and moves.

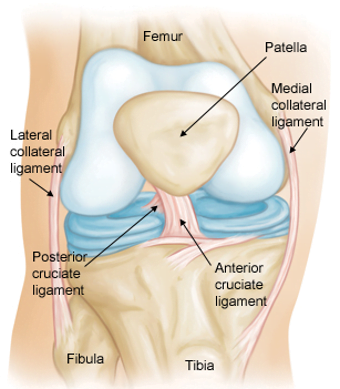

The knee joint is actually made up of two different joints, one large one providing movement between the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia), and one which provides movement between the femur and the kneecap (patella).

The shape of the knee joint does not provide it with much stability, the stability is mainly provided by the ligaments, tendons and muscles (2). If the knee suffers an injury such as a fall or an impact playing sport it is usually these structures which are damaged (3).

What could be causing the pain?

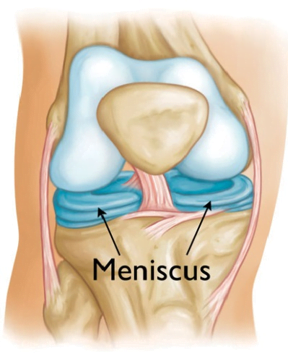

Meniscus tear

The meniscus is made up of two semi-circles of cartilage, they mainly act to reduce friction between the thigh and leg bone, and as shock absorbers (1). They are commonly injured by trauma and  by ‘wear and tear’ over a lifetime and if serious can produce significant pain and loss of motion in the knee. As the meniscus has a poor blood supply it finds it difficult to heal on it’s own, this means that often if there is enough damage a small surgical procedure (arthroscopy) is carried out. Arthroscopies are one of the most common surgeries performed (2), however evidence released in 2017 indicate that arthroscopic techniques have no proven benefit therefore they may no longer be recommended (11).

by ‘wear and tear’ over a lifetime and if serious can produce significant pain and loss of motion in the knee. As the meniscus has a poor blood supply it finds it difficult to heal on it’s own, this means that often if there is enough damage a small surgical procedure (arthroscopy) is carried out. Arthroscopies are one of the most common surgeries performed (2), however evidence released in 2017 indicate that arthroscopic techniques have no proven benefit therefore they may no longer be recommended (11).

In people aged under 50 the cause of a meniscus injury is usually following a fall or a collision in sport or other activity, in the over 50’s it is usually as a result of wear and tear. Females are three times more likely than males to have a problem with their meniscus and a third of people will also have a problem with the ACL ligament (2) (see below).

Traumatic tears are usually accompanied by a small ‘click or snap’ at the time of injury with the pain concentrated horizontally across the joint, there is only swelling 50% of the time and it may be only at the back of the knee. As time progresses there may be a feeling of weakness in the knee and some popping or grinding. The pain may be worse when trying to fully straighten the knee. Meniscal damage due to wear and tear may be very subtle to start with and may only be noticeable during intense activities such as running, twisting on the knee and deep squatting. These symptoms may progress over time until they are similar to the ones seen in a traumatic onset (5).

A meniscus tear can be diagnosed to a good degree of certainty by a health professional such as an osteopath or a doctor, depending on the severity and how long the symptoms have lasted it may or may not be necessary to have medical imaging (usually an MRI) (5). If the damage is not too large then conservative care such as targeted exercise, stretching and activity modification can be prescribed by an osteopath. If the symptoms persist or they become debilitating then surgical intervention may be necessary (2, 5).

Patellofemoral (kneecap) Pain Syndrome

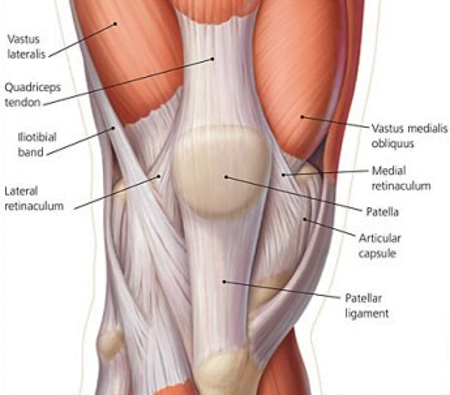

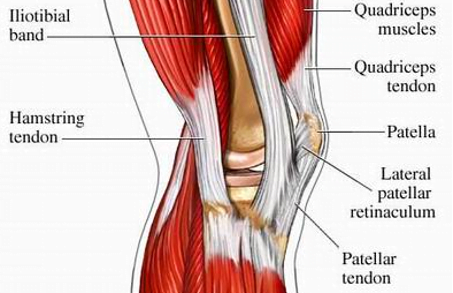

The patella is a bone buried deep in the large tendon of the quadriceps muscles, it’s main function is to be a ‘pulley’ for the quadriceps, it also prevents friction over the knee joint as it is bent (1). As the knee bends the patella increases it’s contact with the femur and moves up in relation to the knee. Any factor that causes the patella to be slightly out of position, or too tight to the femur can cause a series of conditions that are known as Patellofemoral pain syndrome (other names may be ‘jumper’s knee, ‘runner’s knee’, ‘patellar tendonitis’.

The patella is a bone buried deep in the large tendon of the quadriceps muscles, it’s main function is to be a ‘pulley’ for the quadriceps, it also prevents friction over the knee joint as it is bent (1). As the knee bends the patella increases it’s contact with the femur and moves up in relation to the knee. Any factor that causes the patella to be slightly out of position, or too tight to the femur can cause a series of conditions that are known as Patellofemoral pain syndrome (other names may be ‘jumper’s knee, ‘runner’s knee’, ‘patellar tendonitis’.

20% of people who regularly do high impact sports such as running or team sports such as football, netball etc will suffer from pain around the patella, with females twice as likely as males to experience the problem (2).

The position of the patella and the position of the knee joint in relation to the hip and the ankle are both key in working out why a person would be suffering from this problem.

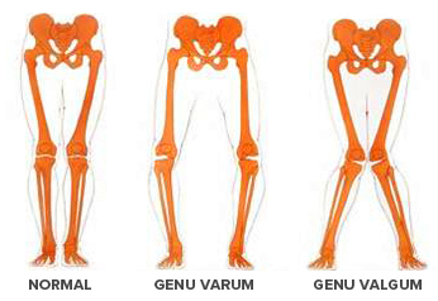

The position of the patella is mostly determined by the amount of strain transmitted through the quadriceps. As the outside (lateral) part of the quadriceps is stronger it is generally considered  that tightness in this area (vastus lateralis and ilio-tibial band) coupled with weakness on the inside part (vastus medialis) can cause the patella to change it’s position and produce pain (6, 2). If the quadriceps are generally tight then this can increase the compression between the femur and the patella causing pain (3). Any change of position of the bones of the lower leg can cause the knee to develop pain, the picture shown below is quite extreme, but it may only take a small change in one hip or leg to produce the pain at the knee joint.

that tightness in this area (vastus lateralis and ilio-tibial band) coupled with weakness on the inside part (vastus medialis) can cause the patella to change it’s position and produce pain (6, 2). If the quadriceps are generally tight then this can increase the compression between the femur and the patella causing pain (3). Any change of position of the bones of the lower leg can cause the knee to develop pain, the picture shown below is quite extreme, but it may only take a small change in one hip or leg to produce the pain at the knee joint.

Tight or weak muscles in the calf, gluteals (buttocks) or abdomen (core muscles) can cause changes in how the knee performs and produce dysfunction and pain (2, 3, 5).

In severe cases there may be damage to the back of the kneecap causing friction and pain, this is called ‘chondromalacia patella’ (1), even at this stage it is still possible to manage with the correct exercise prescription and manual therapy techniques (5).

The same factors of instability or misalignment caused by tightness or weakness in joints and muscles of the lower half of the body can cause ‘iliotibial band syndrome’. This condition mainly affects long distance runners and causes pain at the outside of the knee, especially when running downhill (5). Again, correction of muscle and joint biomechanics, accompanied by rest usually resolves this problem (2).

The same factors of instability or misalignment caused by tightness or weakness in joints and muscles of the lower half of the body can cause ‘iliotibial band syndrome’. This condition mainly affects long distance runners and causes pain at the outside of the knee, especially when running downhill (5). Again, correction of muscle and joint biomechanics, accompanied by rest usually resolves this problem (2).

Ligament injuries

There are four major ligaments in the knee which may become damaged, the anterior cruciate (ACL), posterior cruciate (PCL), the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

There are four major ligaments in the knee which may become damaged, the anterior cruciate (ACL), posterior cruciate (PCL), the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

ACL Tear

The ACL is arguable the most commonly injured ligament in the body (2). It mainly occurs in activities which place a high demand on the knee such as jumping or any sport which involves sharp changes of direction when the knee is bent (rugby, football and skiing) (2). Women are up to 9 times more likely to suffer from a knee injury than men (3).

Typically an ACL injury would happen when landing from a jump, or the foot is planted on the ground, the person tries to turn by pushing off that leg and the knee collapses inwards with an audible ‘pop’. This tends to be extremely painful and will result in it being hard to walk without pain (2, 3). There is usually swelling soon after the onset. An osteopath or your doctor can help diagnose an ACL tear but most (if severe enough) need an MRI to be sure. Rarely would an ACL injury happen in isolation, due to the way the knee bends when the ACL is strained means that the MCL and the meniscus are frequently damage at the same time (3).

In older people, or people who do not wish to be involved in high impact sports that would place the ligament at risk, small ACL tears may be treated with exercise and manual therapy. Most ACL injuries result in surgery to repair the damage (5).

MCL Tear

The MCL is one of the strongest ligaments in the body, however it can be damaged by the knee falling inwards when it is bent (3). It can be as a result of a fall, or just prolonged stress on the inside of the knee caused by weakness in the hip or thigh muscles (1, 6). Small strains will produce pain around the inside of the knee, usually without swelling (3). Larger strains will result in swelling, an increase in the pain and a feeling that the knee is unstable. If the ligament is totally ruptured there is usually damage to the ACL as well, meaning standing on the knee will be difficult. Most small strains resolve with manual treatment and exercises within 8 weeks, but larger ones wold need surgery (5).

PCL Tear

The PCL is a much less common injury than an ACL (10:1) and is usually the result of an impact resulting in the knee being straightened or flexed beyond it’s normal range, or the shin bone being forced back behind the knee by a fall (5). The symptoms depend on the severity of the injury, very slight tears may result in temporary pain and very slight swelling. More severe injuries will have pain behind or in front of the knee, swelling and a pop or click when the injury occurs (2). Most people who suffer PCL injuries (unless very severe) are still able to walk after the onset and may not perceive the injury to be serious. If the knee is unstable or gives way, it must be diagnosed by a medical professional such as an osteopath or a doctor (5).

Slight tears may not limit a person’s activity in the future at all (2), unfortunately many more serious PCL tears do not ever fully recover (90% of function can be restored in partial tears). Surgical intervention remains controversial and may only be recommended when there is damage to other structures in the knee. Exercise and manual therapy can be very effective for management of PCL tears (5).

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.5%20.5)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22silver%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(3.288%20194.97228%20-32.11786%20.54163%2088%20121.6)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%22171%22%20cy%3D%2262%22%20rx%3D%2246%22%20ry%3D%22195%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(178.2%2010%2042.1)%20scale(35.99338%20171.28054)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23acacac%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-14.36696%20.96066%20-6.46117%20-96.62912%2095.3%20174.4)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) LCL Tears

LCL Tears

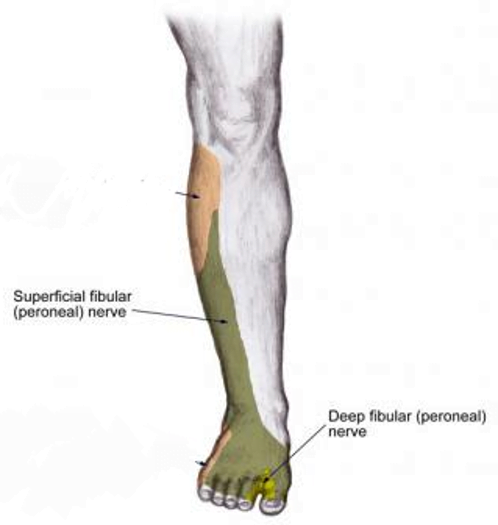

Injury to the LCL is uncommon and is usually the result of a trauma forcing the knee out to the side. Usually as a result of a collision in sport, or a fall (5). As with most ligament injuries, there may be a pop or a click at the time, with some swelling (dependant on severity). Injury in this way may also affect the peroneal nerve which is close by, resulting in some tingling or numbness on the outside of the leg and foot (dark green area in the picture) (2). Mild sprains to this ligament can be easily managed by manual therapy and exercise and most are symptom free within 6 weeks. Severe injuries require surgery and have good success rates, although return to full sports activity is not likely (5).

How Can I Prevent Knee Pain?

Sometimes, accidents happen, especially if playing sports, or engaged in ‘high impact’ activities such as running, and injuries to the knee in these activities are common. However, there are many factors that influence the knee that may either protect it or make it more vulnerable to injury.

Strength in the muscles around the knee will help the knee ligaments deal with the demands placed upon them. For example, the hamstrings and calf muscles are very important in reducing the strain on the ACL when the knee is bent, in a similar way the quadriceps provide resistance to the forces that the PCL has to deal with (2). Weakness in either of these muscles can place the ligaments at risk of injury (5). The balance between the different areas of the quadriceps is also crucial to help the kneecap maintain it’s position and avoid pain (5). Strength in the muscles of the hip (especially the gluteals) can help reduce the likelihood of kneecap and iliotibial band problems (5).

Strength in the muscles around the knee will help the knee ligaments deal with the demands placed upon them. For example, the hamstrings and calf muscles are very important in reducing the strain on the ACL when the knee is bent, in a similar way the quadriceps provide resistance to the forces that the PCL has to deal with (2). Weakness in either of these muscles can place the ligaments at risk of injury (5). The balance between the different areas of the quadriceps is also crucial to help the kneecap maintain it’s position and avoid pain (5). Strength in the muscles of the hip (especially the gluteals) can help reduce the likelihood of kneecap and iliotibial band problems (5).

The hip and the ankle joints both have the ability to produce a wide range of movements, the knee has much less choice in which movements it can perform. This means that to avoid placing excess stress on the knee the hip and ankle need to be as mobile as possible, this has the effect of spreading the load of any movement across all three joints minimizing risk to any one structure (1, 5).

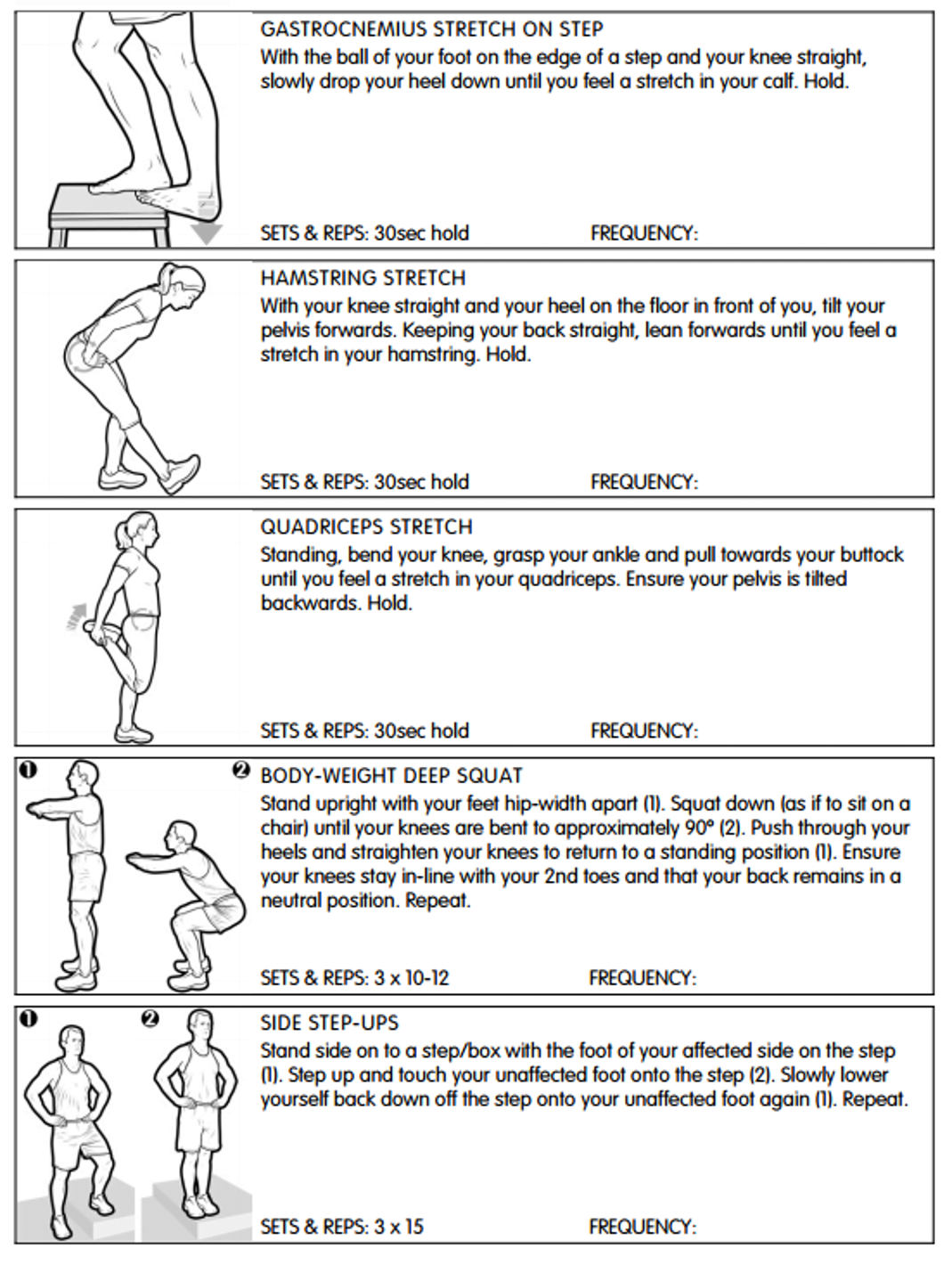

Here’s our top 5 exercises and stretches to do to PREVENT knee pain.

What should I do if I have knee pain?

That all depends on the severity, the onset, and how long you have had the pain. If the onset was traumatic, such as a fall or a collision while playing sport you should get the knee investigated by an osteopath or another health professional to see if there is any structural damage (meniscus, ligaments etc). If there is any instability, or there is a large amount of swelling around the knee then you should seek an accurate diagnosis as soon as possible. (5).

One of the most common questions following a traumatic knee injury is “should I get an x-ray/MRI”? If a health professional assesses you and the answer is yes to one of the following questions then you may be referred to get an x-ray/MRI (4).

1 – Age 55 or over.

2 – Tenderness when pressing on the kneecap.

3 – Tenderness when pressing the top of the fibula.

4 – Inability to bend the knee to 90 degrees.

5 – Inability to take weight on the affected leg for more than 2 paces.

If the problem has been around for a while and it had a slow onset it is still worthwhile getting an assessment and diagnosis from an osteopath to ensure the problem does not persist and begin to inhibit your activity and possibly cause more problems in the future (2, 5).

What is our experience as osteopaths?

As mentioned at the start of this article, due to their structure and function, knees can either be very easy or very difficult to treat effectively. We have had many patients where their knee pain has been severe and longstanding that has been successfully resolved with the correct advice, treatment and exercise prescription, others have had to have been recommended for medical imaging and subsequently surgery. The most important thing is to get a diagnosis and to form an effective plan to deal with the problem,. There is good evidence that osteopathic and other manual techniques are able to help with knee pain (7, 8). An effective knee pain treatment plan also needs to incorporate exercises to maintain range of motion and strengthen muscles in the hips, thighs and lower legs (9, 10) as the source of the problem is often in the surrounding joints and muscles.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References

1 – Levangie, P. and Norkin, C. (2005) Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed). F. A. Davis, Philadelphia.

2 – Magee, D. Zachazewski, J. and Quillen, W., 2009. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, Missouri, Elselvier.

3 – Brukner, P. and Khan, K. (2007). Clinical Sports Medicine (3rd Ed). McGraw Hill, Sydney.

4 – Stiell, I. et al, (1997). Implementation of the Ottowa Knee Rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA, vol 278(27), pp2075-2079.

5 – Carnes, M, & Vizniak, N. (2011). Conditions Manual. Professional Health Systems, Canada.

6 – Souza, T. (2009). Differential Diagnosis and Management for the Chiropractor. 4th ed, Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

7 – Bronfort, G. et al (2010). Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report. Available at, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2841070/, accessed 12/8/15.

8 – Alshami, A. (2014). Knee osteoarthritis related pain: a narrative review of diagnosis and treatment. Available at, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24899883, accessed 14/8/15.

9 – Bolgla, L. et al (2011). An update for the conservative management of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2010. Available at, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3109895/, accessed 18/8/15.

10 – Fransen, M. et al (2015). Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Available at, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3/abstract. Accessed 18/8/15.

11 – Siemieniuk Reed A C et al. (2017) Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline BMJ 2017; 357 :j1982

LCL Tears

LCL Tears