How to stop getting a stitch when running

A stitch when running can be irritating at best, and completely debilitating at worst. The sharp or crampy pain that can occur for a few seconds to a few minutes can ruin plenty of runs! What is a runner’s stitch, what causes it, and how can you stop it from happening? Find out all these things below!

A stitch when running can be irritating at best, and completely debilitating at worst. The sharp or crampy pain that can occur for a few seconds to a few minutes can ruin plenty of runs! What is a runner’s stitch, what causes it, and how can you stop it from happening? Find out all these things below!

What is a runner’s stitch?

A runner’s stitch, or to give it its more technical name ‘exercise-related transient abdominal pain (ETAP) is a common condition observed in people engaged in various sporting activities that has been described as far back as the works of Shakespeare and Pliny the Elder (1, 2). It is commonly described as ‘localized pain that is most common in the lateral aspects of the mid-abdomen along the costal border, although it may occur in any region of the abdomen…it tends to be sharp or stabbing when severe and cramping, aching, or pulling when less intense (3).

Who is more likely to get a runner’s stitch?

Who is more likely to get a runner’s stitch?

Anyone who engages in vigorous physical activity can get a stitch, with runners being the most common group of sufferers (75%), followed by horse-riding (62%), followed by aerobics (52%) (4). Other common activities such as swimming or cycling tended to have much lower rates at 15% and 8% respectively (5).

Age also seems to be a factor with 77% of active people under the age of twenty reporting suffering from a stitch, but only 40% of active people over the age of forty reporting it as being something they experience (5).

Another factor that can influence the occurrence of a runner’s stitch is a person’s level of fitness, although elite athletes still report having a stitch they report it less often than less well-conditioned people (6).

Body type and posture do not seem to have much of an influence on whether or not a person gets a stitch. However, individuals who have increased spinal curves (scoliosis/kyphosis) do seem to have more severe episodes of pain (7).

When a person eats or drinks before activity, it can also be a factor with stitch-like symptoms being more commonly reported if a person has ingested food or fluid just before exercising, this is reported more commonly after ingesting very sugary or salty drinks (4, 8, 11).

What causes a runner’s stitch?

Good question, there have been several different causes investigated to try to find out why a stitch occurs with many of the more commonly cited reasons having no real supporting evidence. Early thoughts were that a stitch was caused by a lack of blood flow to the diaphragm, mechanical stress on the ligaments that support your abdominal organs, digestive problems, or cramps, all of which are not the case (4, 8).

There are three possible contributory factors that may explain why people get a stitch.

- Neurogenic pain – The pain that is commonly described as a stitch can also be produced by mechanical factors in the torso producing pain signals along the intercostal nerve which also produces similar pain in the upper abdomen (9). Running involves a lot of repetitive rotational and compressive forces around the thoracic spine and the ribs, as well as compressing the spine, this can irritate the intercostal nerve and may be a reason why a stitch occurs (10).

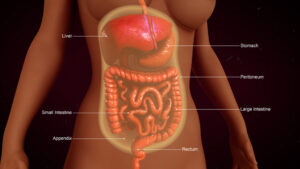

- Irritation of the Parietal Peritoneum – Your parietal peritoneum is the strong connective tissue that surrounds your abdominal organs and forms the underside of your diaphragm. Studies have shown that aggravation of the part of this structure that adheres to the abdominal wall will cause very similar pain to that of a stitch (12). The pain can also be felt in various abdominal locations and can be accentuated by movement and relieved by cessation of movement, all of which are features of a runner’s stitch (13). As younger people have a proportionally larger peritoneal surface it may also explain why a runner’s stitch is more common in that age group (14). Additionally, if the irritation of the peritoneum is the cause of a stitch it would also help explain why you are more likely to get a stitch after eating or drinking as abdominal distension from eating may produce friction (4). In the case of sugary or salty drinks, the peritoneal fluid is highly responsive to osmotic changes in the blood supply that would be seen after consuming such a fluid lending further weight to irritation of the peritoneum as being the source of the pain (15).

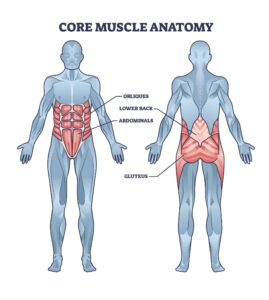

- Lack of core stability – Individuals who suffer from a runner’s stitch have been shown to have significantly less core musculature. The lack of core strength may result in greater abdominal organ mobility during exercise resulting in irritation of the peritoneum (16). This reason may also be why a stitch is more severe in less well-conditioned people.

How do you stop getting a runner’s stitch?

Based on the information above, the literature suggests a few things that might help reduce the likelihood of getting a stitch.

- Avoid eating or drinking large amounts of food or drink within two hours of your activity, especially avoiding very sugary or salty drinks (17). During exercise, small and regular fluid intake may be better than larger amounts.

- Improve your core stability – improving your trunk strength to reduce the forces that may impact the intercostal nerve and reduce abdominal organ movement during exercise could lessen the frequency and severity of the pain (18).

- Improve your spinal mobility and function – Improving the ability of the spine to move properly and maintain good posture has been shown to reduce the incidence of stitches (19, 20).

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor-made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References –

1 – Capps RB. Causes of the so-called side ache in normal persons. Arch Intern Med. 1941;68:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1941.00200070104006

2 – Kugelmass IN. The respiratory basis of periodic subcostal pain in children. Am J Med Sci. 1937;194:376–381. doi: 10.1097/00000441-193709000-00012.

3 – Morton D, Callister R. Exercise-related transient abdominal pain (ETAP). Sports Med. 2015 Jan;45(1):23-35. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0245-z. PMID: 25178498; PMCID: PMC4281377.

4 – Morton DP, Callister R. Characteristics and etiology of exercise-related transient abdominal pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):432–438. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00026

5 – Morton DP, Callister R. Factors influencing exercise-related transient abdominal pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(5):745–749. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200205000-00003

6 – Capps RB. Causes of the so-called side ache in normal persons. Arch Intern Med. 1941;68:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1941.00200070104006.

7 – Morton DP, Callister R. Influence of posture and body type on the experience of exercise-related transient abdominal pain. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(5):485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.10.487.

8 – Sinclair JD. Stitch: the side pain of athletes. N Z Med J. 1951;50(280):607–612

9 – Gallegos NC, Hobsley M. Abdominal wall pain: an alternative diagnosis. Br J Surg. 1990;77(10):1167–1170. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771026.

10 – Leatt P, Reilly T, Troup JG. Spinal loading during circuit weight-training and running. Br J Sports Med. 1986;20(3):119–124. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.20.3.119

11 – Morton DP, Aragon-Vargas LF, Callister R. Effect of ingested fluid composition on exercise-related transient abdominal pain. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004;14(2):197–208

12 – Capps J, Coleman G. Experimental observations on the localisation of pain sense in the parietal and diaphragmatic peritoneum. Arch Intern Med. 1922;30:778–789. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1922.00110120097004

13 – Silen W. Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen. 22. USA: Oxford University Press; 2010.

14 – Esperanca M, Collins D. Peritoneal dialysis efficiency in relation to body weight. J Pediatr Surg. 1966;1(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(66)90222-3

15 – Plunkett BT, Hopkins WG. Investigation of the side pain “stitch” induced by running after fluid ingestion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(8):1169–1175. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199908000-00014.

16 – Mole JL, Bird ML, Fell JW. The effect of transversus abdominis activation on exercise-related transient abdominal pain. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;17(3):261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.05.018.

17 – Morton DP, Richards D, Callister R. Epidemlology of exercise-related transient abdominal pain at the Sydney City to Surf community run. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(2):152–162. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80006-4

18 – Spitznagle TM, Sahrmann S. Diagnosis and treatment of 2 adolescent female athletes with transient abdominal pain during running. J Sport Rehabil. 2011;20(2):228–249.

19 – Kugelmass IN. The respiratory basis of periodic subcostal pain in children. Am J Med Sci. 1937;194:376–381.

20 – Morton DP, Aune T. Runner’s stitch and the thoracic spine. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(2):240. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.009308

Who is more likely to get a runner’s stitch?

Who is more likely to get a runner’s stitch?