How to Get Rid of IT Band Syndrome

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%234d4c4e%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-15.82562%20-116.3647%2044.9216%20-6.10935%2083.7%20130.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(33.72081%20.15758%20-.87272%20186.75626%20183.7%20165.6)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-4.1%202666%2071.4)%20scale(34.40969%2096.76449)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23666%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M32.2%2040.4h105.5v54H32.2z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) Knee pain when running – Iliotibial Band Syndrome

Knee pain when running – Iliotibial Band Syndrome

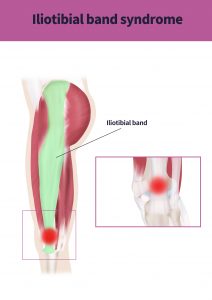

The most common site of pain and injury for runners is the knee (1), and a very common condition that can happen to a runner’s knee is what is called Iliotibial Band (ITB) Syndrome. This condition is the most common lateral knee condition in runners, making up 14% of all injuries in this area. It is usually felt on the outside of the knee and the calf when running or descending stairs and can either be a stiff/dull pain or a more intense stinging or burning pain. The pain usually appears after a certain time running, limiting the duration of a runner’s activity (2). In this article we will be explaining what an ITB is, why it can cause pain in runners, and how you can guard against it producing pain as well as what to do if you already have ITB related pain.

What is an iliotibial band?

The iliotibial band is a strong and dense layer of connective tissue that lies on the outside of the thigh, at its top end it arises from and is part of, the gluteus maximus and the tensor fascia lata (two muscles that help move the hip). At it’s lower end it covers the lateral femoral epicondyle, just above the knee on the outside of it, and attaches just below the knee on the tibia. During the foot-strike phase of running the action of deceleration that is in part performed by the gluteus maximus and the tensor fascia lata generates tension in the iliotibial band (3).

Why does it cause pain on the outside of the knee?%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%238f113b%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(189.24619%20-.80378%20.11842%2027.88206%20110.9%208.2)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(42.89624%20-205.33272%2079.35865%2016.57889%20140.3%20256.6)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23acadac%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(27.88425%202.12299%20-5.6084%2073.6633%2059.7%20158.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(171.8%2031.6%20143)%20scale(208.22125%2051.38533)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

When the knee is bent and then subsequently straightened again in a repetitive manner (such as running or cycling) it has been suggested that the fibres of the iliotibial band can ‘rub’ over the lateral femoral epicondyle, and therefore cause friction on the outside of the thigh just above the knee. This results in a stinging or burning pain at the site of the friction whenever load, such as weight-bearing during running, is applied to the knee (2).

Why are only some runners affected?

There are several factors that are thought to contribute to the development of ITB friction syndrome;

- Doing too much too soon – It has been shown that runners who have a high mileage relative to their experience will have an increased risk of developing ITB friction syndrome (4). This tallies with research that shows that one of the biggest risk factors for running injuries, in general, is being a beginner at the activity (5).

- Hip and thigh strength (4, 6) – Most authors agree that runners who suffer ITB friction pain exhibit weakness in the major muscles used for running. Some studies have shown that quadriceps and hamstrings are implicated (4), others that the muscles responsible for hip abduction are not performing correctly (6).

- The two factors above are thought to be inter-related if you have high weekly mileage and strength deficits in the muscles you use for running then you are even more likely to develop ITB friction syndrome (4). This fits with what we know about ITB syndrome in relation to when symptoms appear, often people who have this condition will be able to run up to a certain distance or time, then they begin to get pain. This may indicate a fatiguing of the muscles being used to run leading to a change in how the hip and knee perform (6).

- Type of running – track and distance runners are thought to be more vulnerable to ITB friction pain as the nature of the activity tends to be in a forward direction with little need to change direction side to side. It has been suggested that this leads to a lack of strength in the muscles used for hip abduction (4, 6).

How do I get rid of the pain?%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.6%20.6)%20scale(1.17188)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23adadad%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(7.0011%2061.75306%20-27.73017%203.14384%20181%2045.5)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%22255%22%20cy%3D%22100%22%20rx%3D%2244%22%20ry%3D%22121%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23a6a6a6%22%20cx%3D%2268%22%20cy%3D%2263%22%20rx%3D%2228%22%20ry%3D%2239%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%227%22%20cy%3D%2295%22%20rx%3D%2214%22%20ry%3D%22111%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

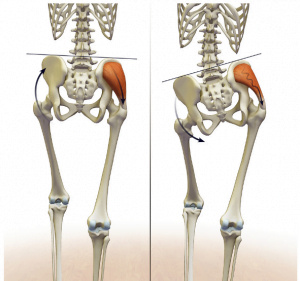

The first step is to get an accurate diagnosis, ITB friction syndrome is not the only condition affecting the outside of the knee, lateral ligament strains, hamstring tendinopathies, and lateral meniscus problems should be ruled out before beginning a treatment program (7). Diagnosis can be made without the use of imaging (MRI or x-ray) by considering a person’s training history when the pain occurs, and evaluation of the knee and surrounding joints and muscles (8). A thorough assessment would also include an analysis of how the knee performs when a person performs activities on one leg, such as single-leg balances and small knee bends while standing on one leg. By evaluating what happens to the knee in these activities it is possible to begin to see where the problem lies with a runner’s biomechanics (9). Often a runner with ITB friction pain will exhibit a ‘hip hitch’ pattern where the pelvis tilts when running which causes the knee to fall in towards the midline (as seen in the right-sided image here) (9).

Once an accurate diagnosis has been made the most commonly recommended course of action is threefold;

1 – To release tight areas of the hip (specifically the gluteal muscles and the tensor fascia lata), quadriceps and hamstrings, either through manual therapy or stretching/foam rolling. It is not possible to stretch or manipulate the iliotibial band directly due to the very tough nature of its structure, but working with the muscles that influence it can result in an easing of symptoms (10).

2 – A review of the runner’s training history or habits to see if there are any training errors such as increases in distance or terrain changes that may have overloaded their biomechanics, often making adjustments here can mean that they can continue to run without aggravating the problem.

3 – Strength exercise prescription is generally considered to be the crucial aspect in resolving ITB friction pain, there is good evidence that strengthening the abd uctors of the hip will result in a reduction in symptoms, this is because these muscles help control the position of the knee and pelvis during the foot-strike phase of running (reducing the ‘hip hitch’ pattern). There may also be other areas that need to be strengthened to further reduce the symptoms, such as the hamstrings and the core muscles (6, 9). Once the individual muscles are more powerful it is necessary to incorporate more running-specific exercises to make the new strength transfer into running performance.

uctors of the hip will result in a reduction in symptoms, this is because these muscles help control the position of the knee and pelvis during the foot-strike phase of running (reducing the ‘hip hitch’ pattern). There may also be other areas that need to be strengthened to further reduce the symptoms, such as the hamstrings and the core muscles (6, 9). Once the individual muscles are more powerful it is necessary to incorporate more running-specific exercises to make the new strength transfer into running performance.

By addressing these elements most runners will show significant improvements in their symptoms within a few weeks. Each runner’s needs are different, a comprehensive history of their activity coupled with a tailored rehabilitation program will produce the quickest results (9).

In our clinic, we have helped scores of runners either get over chronic injury or improve their performance. We use strength, endurance, and core stability testing, as well as analysis of training schedules and running styles, to help runners of all abilities to achieve their goals pain and injury-free. We can provide individualised treatment plans and exercise programs to suit all needs.

Is an injury stopping you from running, or has pain stopped you from achieving your running goals? If so why not book a running injury consultation with our expert osteopath Jay Ruddock.

Please visit our resource section for a basic ITB friction syndrome exercise protocol which is a good starting point if you think you may have ITB pain. If you want to test yourself to see if you have the right amount of muscular strength to avoid running injuries then you can read our article and download our guide to testing here.

References –

1 – van der Worp, M. P., ten Haaf, D. S., van Cingel, R., de Wijer, A., Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W., & Staal, J. B. (2015). Injuries in runners; a systematic review on risk factors and sex differences. PloS one, 10(2), e0114937. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114937

2 – van der Worp M. P., van der Horst N., de Wijer A., Backx F. J., Nijhuis-van der Sanden M. W. ,(2012). Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 42(11):969-92

3 – Fairclough, J., Hayashi, K., Toumi, H., Lyons, K., Bydder, G., Phillips, N., … Benjamin, M. (2006). The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of anatomy, 208(3), 309–316. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00531.x

3 – van der Worp M. P., van der Horst N., de Wijer A., Backx F. J., Nijhuis-van der Sanden M. W. ,(2012). Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 42(11):969-92

4 – Messier S. P., et al. (1995). Eitiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: July – pp 951-960.

5 – Taunton J.E, Ryan M.B, Clement D.B, McKenzie D.C, Lloyd‐Smith D.R, Zumbo B.D, (2002). A retrospective case‐control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br. J. Sports Med; 36(2): 95–10

6 – Fredericson, M., et al (2000). Hip Abductor Weakness in Distance Runners with Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 10. 169-75.

7 – Khaund R, Flynn SH. (2005). Iliotibial band syndrome: a common source of knee pain. American Family Physician. 71(8):1545-1550.

8 – Michael D. (2008). Clinical Testing for Extra-Articular Lateral Knee Pain: A Modification and Combination of Traditional Tests. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 3: 107–109.

9 – Hobrough, P., (2016). Running Free of Injuries. Bloomsbury, London.

10 – Baker RL, Fredericson M. (2016). Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners : Biomechanical Implications and Exercise Interventions. Physical médicine and réhabilitation clinics of North America, 27(1):53-77

Knee pain when running – Iliotibial Band Syndrome

Knee pain when running – Iliotibial Band Syndrome