Ankle Sprain – How bad is it and what should I do?

The ankle is the most commonly injured joint among athletes (1), however it can happen to anyone. Ankle sprains account for 85% of all ankle injuries (1). Many of us have sprained an ankle and needed very little recovery time, maybe a few days to get over it, however ankle sprains can range from the innocuous to the severe and debilitating with as many as 40% of them going on to become chronic problems (2). This article is intended to give you an idea of what happens when you sprain an ankle and what to do if it doesn’t get better in a few days.

The ankle is the most commonly injured joint among athletes (1), however it can happen to anyone. Ankle sprains account for 85% of all ankle injuries (1). Many of us have sprained an ankle and needed very little recovery time, maybe a few days to get over it, however ankle sprains can range from the innocuous to the severe and debilitating with as many as 40% of them going on to become chronic problems (2). This article is intended to give you an idea of what happens when you sprain an ankle and what to do if it doesn’t get better in a few days.

Who is most at risk of a sprain?

- Athletes who perform ‘high impact’ sports, especially rugby, basketball, football and off-road running. These activities place a high demand on the ankle joint due to impact and the rotation of the person’s weight over their ankles.

- People who take very little exercise meaning their ankles lack the stability and support needed to cope with the demands of movement.

- Risk is further increased by tight calf muscles and an imbalance in the muscles on the inside and outside of the lower leg.

- People who perform activities on uneven surfaces.

- Athletes who fail to warm up properly or do not invest in appropriate footwear for their activity.

- People with a history of previous ankle sprains. (1, 3)

What happens when you sprain an ankle?

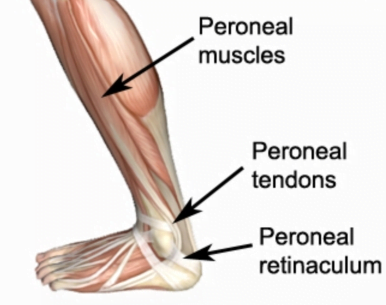

The vast majority of ankle sprains are ‘inversion’ sprains meaning that the affected ankle is turned inwards towards the opposite foot and the person’s weight moves towards the outside of the foot. This places too much strain on the ligaments (mainly the anterior talo-fibular and distal tibio-fibular) and muscles (peroneals) on the outside of the foot resulting in damage (4).

The vast majority of ankle sprains are ‘inversion’ sprains meaning that the affected ankle is turned inwards towards the opposite foot and the person’s weight moves towards the outside of the foot. This places too much strain on the ligaments (mainly the anterior talo-fibular and distal tibio-fibular) and muscles (peroneals) on the outside of the foot resulting in damage (4).

Most people will have felt the ankle ‘go over’ and will hear/feel a small pop or tearing sensation depending on how severe the sprain is. Most people will be able to stand on the ankle just after it is sprained, it may even be possible with a severe sprain to keep running walking on it. If you cannot place any weight on the ankle it may indicate that there is a fracture (usually of the smaller shin bone, the fibula) (5).

After the sprain the ankle may feel unstable or it may not feel like it did before the sprain, this is a standard response as the biomechanics of how the ankle moves have changed. There may also be some bruising appear immediately or after a day or two, this may indicate a more severe sprain or possibly a fibular fracture.

After the sprain the ankle may feel unstable or it may not feel like it did before the sprain, this is a standard response as the biomechanics of how the ankle moves have changed. There may also be some bruising appear immediately or after a day or two, this may indicate a more severe sprain or possibly a fibular fracture.

How can I tell how bad it is and what should I do?

Ankle sprains are divided up into three grades, I-III depending on their severity.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.5%20.5)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23aa7f8e%22%20d%3D%22M105%20209.7l-25-65.3%20141-54.1%2025%2065.3z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-106.4%2060.4%20-14.4)%20scale(73.04855%20160.77807)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%2250%22%20cy%3D%22202%22%20rx%3D%2285%22%20ry%3D%2228%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23bf6b88%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(69%20-35.7%20190.9)%20scale(17.15779%2034.11625)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) Grade I

Grade I

A mild sprain with mild pain and little swelling, some joint stiffness may be apparent. This is usually a minor tear to a ligament that doesn’t result in any laxity of the ligament. This commonly resolves in a few days with some careful movement needed in the short term. As mentioned above there may be some change as to how the ankle performs and some mild straining of the peroneal muscles which may need some treatment to resolve. Evidence suggests that anti-infammatory medication may be used to reduce pain and swelling but their use may delay the healing process(9).

Grade II

Moderate to severe pain, notable swelling with joint stiffness. This is likely to indicate a partial tear of one or more of the ligaments, this is indicated by difficulty walking or flexing the foot upwards towards the knee. This type may take 2-3 months to fully resolve using manual therapy such as osteopathy and carefully prescribed exercise to help retrain the ankle to return to full mobility and stability.

Grade III

Severe pain initially possibly followed by a little or no pain as the nerves may be disrupted, sizeable swelling is seen and stiffness occurs hours after the injury. In this type there is complete tearing of the ligaments resulting in complete loss of function (usually the person needs crutches). Can take over 4 months to resolve, a small amount of cases need surgery, although most will be repairable through manual therapy and exercise prescription (5).

You should seek medical help (doctor, walk in centre or hospital) if you cannot put any weight on the affected ankle or the foot goes very cold, turns pale, or goes numb (4).

What you should do depends on how severe the sprain is, although in the very short term it is advised that the R.I.C.E first aid principles are used.

Most sprains show some swelling, once the swelling begins to subside it is advised that you seek help (from an osteopath or a doctor) to diagnose the type and severity of the sprain. It is possible to begin treatment within 72 hours of the sprain occurring (4).

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%237b6712%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(27.04212%20-56.49358%20260.40942%20124.65173%2066.6%20190)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dbd4de%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-56.33306%20-105.50245%2083.0266%20-44.33208%20133.6%20.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dd6e94%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(17.89896%20-37.7814%2088.9997%2042.16365%20150.3%20136.3)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239aabba%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-140.7%20149.8%20-8.1)%20scale(87.41933%2077.36226)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) What treatments can help?

What treatments can help?

With most sprains of grade I and II, treatment designed to increase ranges of motion is more beneficial than immobilisation, so getting help is better than doing nothing (6) ! Even grade III sprains have been shown to have quicker resolution and less stiffness if treated with exercise as opposed to surgery (6). Range of motion exercises and gentle techniques performed by an osteopath can help improve the mobility in the ankle joints in the early stages (7), then as soon as possible the focus should shift to a more exercise based programme (9). With any ligament injury it is crucial to follow a structured programme of graded exercise to restore the strength to the surrounding muscles and stability to the ligaments, these start with simple balance exercises and then progress to more ‘sports specific’ exercises if necessary (7). If the injury shows no sign of improving then you may need an x-ray or other imaging to determine why.

When can I return to activity?

Ligaments take longer to heal than other soft tissues in the body due to their relatively poor blood supply (8), however with grade I and II ankle sprains people often return to full activity within a few weeks (with or without treatment). This is possibly why many people suffer relapses and further sprains. People who suffer an ankle sprain are strongly recommended to carry out at least four weeks of prescriptive exercise and rehabilitation, this can reduce the incidence of reoccurrence by 50% (7). If the sprain was grade I or II then there is good evidence that athletes returning to sport should tape or brace the ankle for a minimum of 6 months.

Ligaments take longer to heal than other soft tissues in the body due to their relatively poor blood supply (8), however with grade I and II ankle sprains people often return to full activity within a few weeks (with or without treatment). This is possibly why many people suffer relapses and further sprains. People who suffer an ankle sprain are strongly recommended to carry out at least four weeks of prescriptive exercise and rehabilitation, this can reduce the incidence of reoccurrence by 50% (7). If the sprain was grade I or II then there is good evidence that athletes returning to sport should tape or brace the ankle for a minimum of 6 months.

What is our experience as osteopaths?

Ankle sprains are one of the most common things we see in our clinic. They are relatively easy to diagnose and an effective treatment plan is usually straightforward to design and carry out resulting in full resolution of the problem. Sadly our experience is that many patients fail to either seek help, or fail to complete the recommended rehabilitation programme resulting in relapses. Repetitive sprains can further damage the structures of the ankle and may lead to problems further up the body, especially knees, hips and the low back. We are very successful in treating ankle sprains in the short and medium term, and we regularly treat patients who have had multiple sprains and even fractures going back years that have resulted in ongoing pain and limited performance.

Treating an ankle sprain is only successful with teamwork! In the early phases of treatment the focus is mainly on us as the therapist supplying good advice and applying effective techniques to restore movement but the later phases are mostly relying on the patient to keep up with their exercises and to be cautious when returning to sport. The main mistake people make is thinking that once the pain has gone then the ankle is fine to use as before when there may still be dysfunction and instability in the ankle resulting in relapses and further sprains. What we recommend to our patients is;

- Seek help early to improve long term outcomes

- Recognise that it is better to complete one full rehabilitation programme to avoid relapses and return the ankle to full function.

- Get treatment/modify activity in order to address the risk factors that may have contributed to the ankle sprain in the first place.

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References

- Seffinger, M. and Hruby, R., 2007. Evidence Based Manual Medicine – A Problem Based Approach. Philadelphia, Elselvier.

- Bennett, W, F, 1994. Lateral Ankle Sprains. Part 2, Acute and Chronic Treatment. Orthop Rev, 23:504-510.

- Barker H, B, et al, 1997. Ankle injury risk factors in sports. Sports Medicine, 23, pp69-74.

- Carnes, M, & Vizniak, N. (2011). Conditions Manual. Professional Health Systems, Canada.

- Wolfe, W, M, 2001. Management of ankle sprains. Available at; http://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0101/p93.html

- Kerkhoffs G, M, et al, 2002) Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst, 3:CD003762.

- Magee, D. Zachazewski, J. and Quillen, W., 2009. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, Missouri, Elselvier.

- Snell, R. et al (2008). Clinical Anatomy by Regions (8th edition). Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

- Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, et al. (2018). Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: updae of an evidence-based clinical guideline, Br J Sports Med;52:956.

Grade I

Grade I What treatments can help?

What treatments can help?