How old is too old for osteopathic treatment?

We were searching round for a good topic for another article for this month, so we decided to ask some of our patients what they would be interested in reading. One idea that really grabbed us was ‘how old is too old to be having osteopathic treatment’? In this article we attempt to answer this question and examine treatment options for some of the more elderly members of our society.

Depressingly, our bodies are beginning decline in terms of physical potential around the age of 30, this can be measured by looking at strength, cardiovascular performance and reaction time (1). After 30, it is a general rule of thumb that we lose 1% of our physical potential per year (1). However, we all age at different rates, with genetics, activity levels, and life events such as illness or trauma having an impact on how well our bodies cope with getting older. For example, a person who continues to do cardiovascular exercise such as cycling as they get older tend to have 50% less decline than those who are sedentary (1).

Depressingly, our bodies are beginning decline in terms of physical potential around the age of 30, this can be measured by looking at strength, cardiovascular performance and reaction time (1). After 30, it is a general rule of thumb that we lose 1% of our physical potential per year (1). However, we all age at different rates, with genetics, activity levels, and life events such as illness or trauma having an impact on how well our bodies cope with getting older. For example, a person who continues to do cardiovascular exercise such as cycling as they get older tend to have 50% less decline than those who are sedentary (1).

In our experience people say ‘it’s because I’m getting older’ more when they get into their mid to late 40s, this may be because they have begun to experience some joint stiffness, or notice they can’t quite perform to the mental or physical level that they are used to. As time goes on our body’s structure begins to change, joints may lose their smooth cartilage surfaces leading to arthritis, the muscles and tendons become less elastic due to changes in their chemistry and later in life the bones can lose density leading to osteoporosis (2). These changes lead to changes in posture, ranges of movement and levels of pain experienced on movement.

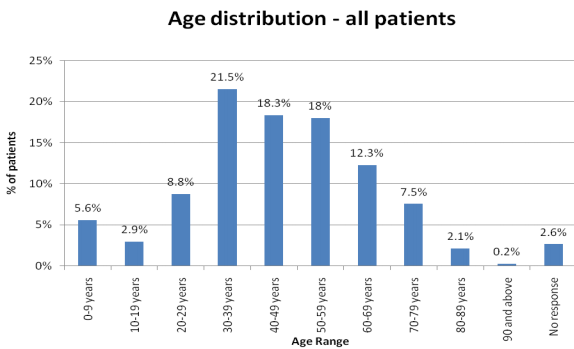

The graphic below shows what the age groups of people in the UK that visit osteopaths (3). The most common time of life to do so is between 30 and 60. This may be due to the fact that people are feeling stiff and uncomfortable but still active enough to want to continue their hobbies and activities.

The graphic below shows what the age groups of people in the UK that visit osteopaths (3). The most common time of life to do so is between 30 and 60. This may be due to the fact that people are feeling stiff and uncomfortable but still active enough to want to continue their hobbies and activities.

The good news is that as people get older there are lots of things that can help slow the decline and help keep them active and pain free.

As mentioned earlier, physical activity is key to remaining as healthy as possible as we get older. For instance we all are probably aware that aerobic exercise will help you maintain a healthy heart and lungs, but did you know that it also protects against the loss of cognitive functions such as memory, processing speed and decision making as well (4)? But it is not just aerobic exercise that can help us lead longer and healthier lives, a large study in 2008 showed that men who demonstrate higher levels of strength are more likely to live longer, and this effect is increased if they already have a good level of cardiovascular health (5). So what that boils down to is if you want to stay sharp and prolong life one way to do so is to maintain an exercise programme that is a mix of aerobic activity and strength training.

Anyway, back to our original question, is there an age at which osteopathy or manual therapy becomes less useful? The answer is that almost all of the time we can still treat someone no matter what age they are, however, what we treat, how we treat, and how we assess them will change as a person gets older. When a person gets over 65 they would technically be classed as a geriatric, however as people live healthier and longer lives a person may not be treated as a geriatric until they are 70-75 (6). The descriptions below are mainly to do with the treatment of geriatrics.

As you may imagine we don’t get too many sports injuries (but we still get some) in people over 70, but we do see a lot of people suffering from osteoarthritis, problems to do with posture, mobility, and osteoporosis. The reason we are able to help people suffering with the above ailments is that the outcomes for people in their 70s are usually different from people from a younger age group. For instance, osteopathic treatment for osteoporosis is not intended to reverse the loss of bone density but to reduce the risk of falls and therefore possible fracture. We can do this by giving appropriate balance and reaction exercises, alongside treatment to help alleviate a stooped posture (which limits the visual field and increases postural instability); we can also increase mobility in the ankles and knees to increase the person’s ability to arrest a fall. The less falls they have, there is less risk of fracture and less risk of the loss of independence. (7)

As you may imagine we don’t get too many sports injuries (but we still get some) in people over 70, but we do see a lot of people suffering from osteoarthritis, problems to do with posture, mobility, and osteoporosis. The reason we are able to help people suffering with the above ailments is that the outcomes for people in their 70s are usually different from people from a younger age group. For instance, osteopathic treatment for osteoporosis is not intended to reverse the loss of bone density but to reduce the risk of falls and therefore possible fracture. We can do this by giving appropriate balance and reaction exercises, alongside treatment to help alleviate a stooped posture (which limits the visual field and increases postural instability); we can also increase mobility in the ankles and knees to increase the person’s ability to arrest a fall. The less falls they have, there is less risk of fracture and less risk of the loss of independence. (7)

As we get older the soft tissues and joints of our body change to have the effect of limiting our movement (8), this means we are less able to move as expansively as before making everyday activities such as stair climbing and getting in and out of a car more difficult. A gentle form of manual therapy known as joint articulation can help increase the range of motion possible at specific joints, in specific ways to allow easier and less painful movement. It may sound like small targets, but to the elderly, things like being able to climb stairs and drive a car are extremely important in maintaining an independent lifestyle.

When our patients are in the younger age group then most of the time it is easier to determine if the pain they are having is from a musculoskeletal source, e.g. a joint or muscle. In geriatric people there are a host of things that may cause pain and discomfort, such as underlying diseases, structural changes in bones and joints, or even side effects from the medications that are more commonly prescribed to the elderly (2). Often our assessment for an elderly person will be more wide ranging in order to establish a ‘baseline’ of how they are at the start of treatment, we can then monitor any change over time and see if the changes we see are as expected with the aging process or if they are more sudden which may indicate a problem that needs further investigation. How we measure an elderly person’s capacity is also slightly different to the younger age group in that we try to relate our questions to relevant daily activities such as cleaning, stair climbing and how far they can walk when outside. This information gives us a good idea about how much treatment or exercise prescription they can cope with. We also feel it is important to get to know the needs of our elderly patients in terms of their social structures and their mental state so we can advise of specific support resources that they may find useful.

When our patients are in the younger age group then most of the time it is easier to determine if the pain they are having is from a musculoskeletal source, e.g. a joint or muscle. In geriatric people there are a host of things that may cause pain and discomfort, such as underlying diseases, structural changes in bones and joints, or even side effects from the medications that are more commonly prescribed to the elderly (2). Often our assessment for an elderly person will be more wide ranging in order to establish a ‘baseline’ of how they are at the start of treatment, we can then monitor any change over time and see if the changes we see are as expected with the aging process or if they are more sudden which may indicate a problem that needs further investigation. How we measure an elderly person’s capacity is also slightly different to the younger age group in that we try to relate our questions to relevant daily activities such as cleaning, stair climbing and how far they can walk when outside. This information gives us a good idea about how much treatment or exercise prescription they can cope with. We also feel it is important to get to know the needs of our elderly patients in terms of their social structures and their mental state so we can advise of specific support resources that they may find useful.

We hope this article shows that osteopathic treatment can benefit people of all ages, the style of treatment may change, but our osteopaths have the skills to accurately assess and treat people in their old age. Oh, and if you want to know, our oldest patient is 93…….

Do you want to know what is causing your pain and if we can help? Why not take advantage of our new patient assessment introductory offer to get you started towards a tailor-made recovery plan for only £19.

Are you in a lot of pain and want to get better as soon as possible? If so then why not book in for a new patient consultation, with treatment on the day, for £75.

We are also there to help you from home. Take a look at our suite of exercise resources and advice sheets which you can easily download and use from home.

References

1 – Gabbard et al, 1992. Lifelong Motor Development. W.C. Brown, Dubuque IA.

2 – Souza, T. (2009). Differential Diagnosis and Management for the Chiropractor. 4th ed, Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

3 – National Council for Osteopathic Research, 2010. The Standardised Data Collection Project. [online], available at, http://www.osteopathy.org.uk/resources/research/.

4 – Hayes, S. M., Alosco, M. L., & Forman, D. E. (2014). The Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Cognitive and Neural Decline in Aging and Cardiovascular Disease. Current Geriatrics Reports, 3(4), 282–290. http://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-014-0101

5 – Ruiz, J. R., Sui, X., Lobelo, F., Morrow, J. R., Jackson, A. W., Sjöström, M., & Blair, S. N. 2008.. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 337(7661), 92–95. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a439

6 – Besdine, R. 2016. Merck Manual (Professional Edition). Available at; http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/geriatrics/approach-to-the-geriatric-patient/introduction-to-geriatrics

7 – Nelson, K. Glonek, T. 2007. Somatic Dysfunction in Osteopathic Family Medicine. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

8 – Magee, D. Zachazewski, J. and Quillen, W., 2009. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, Missouri, Elselvier.